The Antique Silver Industry of Hanau

Part 2

From the middle to the end of the nineteenth century copies of old

silver, and items designed in an amalgamation of historic styles,

satisfied customer demand and preference. Many firms (click

note 1) in Europe and in the United States produced this type of

silver. Generally speaking, the recognition of reproduction silver does

not present a problem since it is marked according to the laws of the

country of origin.

Contrary to this, the antique silver industry of Hanau chose to mark its

output with fantasy marks. It is difficult to say if this was practiced

with a clear intent to deceive. But it is strange that the spurious

marks somewhat resemble old marks, and are also harmonized with the

style of the piece. For example, French rococo style reproductions are

marked with French looking marks, German seventeenth century-inspired

pieces got German-looking marks, and so on. Furthermore, most Hanau

firms chose as company marks styles reminiscent of seventeenth and

eighteenth century maker's marks.

The diary of Willi Rodde, son-in-law and successor to August

Schleissner, describes prevalent practices of the Hanau silver industry,

ca. 1935

(click note 2). Stories of how antique silver was borrowed and

copied exactly down to the old marks follow descriptions of visits by

the German Empress to Schleissner's showrooms, where she purchased some

silver items. Rodde remarks that, even though the Empress was told that

her purchases were exact copies of antique silver, he is sure that these

items would be registered as authentic in the imperial inventories

(click note 3). He describes how some retailers ordered pieces

devoid of any marks. Others, like Bulgari in Rome, ordered table silver

with English-looking marks, which he loved to sell to English customers.

Truth or legend, the fact that this is the diary of the CEO of one of

Hanaus's leading manufacturers, and that it was left unpublished, seems

to lend the stories credibility.

Mark stamping as practiced in Hanau would have been completely illegal

in France or England, or for that matter in any other German city where

a guild supervised the marking. But Hanau had a long tradition as a

free-trade city

(click note 4). In Hanau, silver production was a business

proposition, rather than being dependent on the grant of master status

by a goldsmiths guild or corporation. Stamping of silver wares by

wardens was discontinued in Hanau by the end of the eighteenth century,

and, from 1874, the Hanau town mark was not used anymore. Research has

shown that Hanau silversmiths had already used fake Nuremberg marks in

the seventeenth century, and there were numerous court cases against

Hanau silversmiths in the eighteenth century for stamping their wares

with spurious Nuremberg and Augsburg marks

(click note 5). Furthermore, the imperial law of 1888 abolished

official stamping by wardens in all of Germany. From then on every

producer stamped his own wares and used guaranty marks for the required

silver content. This again put the stamping methods of the Hanau silver

industry within the framework of the law.

It is thanks to the extensive research of Dr. W. Scheffler that the

spurious Hanau marks were catalogued and pictured for the first time.

Ongoing research will probably add to this catalog many more spurious

marks used in Hanau. Products of the antique silver industry of Hanau

have long been a source of confusion for auction houses and antique

dealers, as evidenced by Dr. Scheffler's long lists of items that were

misattributed and sold as genuine

(click note 6).It may be of small comfort to the collector that even

the most esteemed experts are sometimes fooled by Hanau pieces

(click note 7).

Before discussing the different types of spurious marks, it should be

mentioned that Hanau was not the only "antique silver" producing center.

Schoonhoven and Groningen in the Netherlands, had similar thriving

industries which also stamped their wares with fantasy marks. These are

published in K.A. Citroen, Valse Zilvermerken in Nederland (Amsterdemna,

New York, Oxford 1977, call numbers Library of Congress 76-22679;NK

7154.A1 C57; ISBN O-7204-0522-Y).

The advice most often given to collectors, to familiarize themselves

with styles and the way things were made, is of course good and

pertinent. Everyone who has worked for years to become an expert, by

reading and by inspecting and handling silver, can appreciate it. The

following remarks are not meant to replace serious study, but rather to

give some helpful pointers for collectors who do not have access to a

copy of Dr. Scheffler's book.

From all groups of fantasy marks, the "English prestige marks" are the

easiest to recognize. Because English silver is so widely researched and

published, even a cursory comparison will suffice to identify the

reproduction. Next is the group of German-looking marks. The imperial

law of 1548 decreed the use of a town mark and a master mark

(click note 8).) Although Hanau items with two or three marks do

exist, most of them feature a riot of marks. Up to nine punches were

often used on the same silver item, many of which could qualify as town

marks. The most common mark on Neresheimer silver is the German

Renaissance "n", while Schleissner featured eagle-and-crown combinations

and, as the company mark, a sickle in a shaped surround.

For items inspired by French styles, mostly Louis XIV and XVI,

French-looking marks were used. The most frequent are the plain or

crowned fleur-de-lys, and crowned date letters. Schleissner used crowned

master marks with the letter combinations BI or RC. Another maker, Georg

Roth & Company, used a crowned GR. Neresheimer used a TG below the

fleur-de-lys. All of these French-looking marks are very shallow, in

contrast with genuine early French marks, which were punched forcefully

and deeply while the item was still in a rough state, so that they would

withstand the finishing process intact. Furthermore, genuine French

pieces have "recharge" marks, which are tiny and mostly found on the rim

of the piece

(click note 9). This leads to another guideline: Old silver has

recharge and tax marks which reproductions lack, and the reproduction

pieces often have import marks from which old silver was exempted.

The portion of Hanau production comprising exact copies of authentic old

silver, and left unmarked, presents a problem for the art historian, who

comes more and more to rely on the help of natural sciences. Metallurgic

analysis often reveals metal alloys that prove a nineteenth century

manufacture. We know that Hanau firms smelted old coins and old silver,

(click note 10). a fact that seems to defeat metallurgic tests. But

fortunately, one metal unknown before the nineteenth century found its

way into the melting pots of the silversmiths. This rare metal,

extracted first in 1817 from zinc ores, is cadmium. Today, the use of

cadmium has been largely abandoned because of its carcinogenic

properties. From the middle of the nineteenth century, it was widely

used as an ingredient in gold and silver alloys, as well as in hard

solder. For authenticity analysis, cadmium is regarded as a

"fake-indicator." The presence of cadmium shows that presumed old

objects are really nineteenth production, or have at least been

substantially altered or repaired

(click note 11).

The collector must be aware of two facts: Wars and financial crises have

greatly diminished antique Continental silver, and only a small

percentage of the original production has survived. On the other hand,

the output of the Hanau antique silver industry was prolific. Clever and

active marketing found ever new customers all over the world. Hanau

silver was even exported to Africa, Siam, and China, and forms a large

part of available antique silver everywhere. Therefore, the chance of

finding a nineteenth or twentieth century item or reproduction silver is

incomparably higher than of finding the rare genuine piece.

Illustrations

|

|

Chased tankard by Schleissner

ca. 1880, 43 cm

|

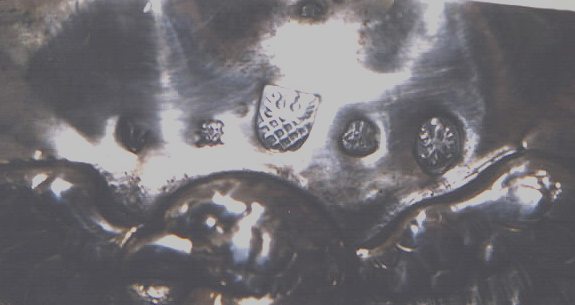

Marks on tankard on the left. The TS mark

is remarkably similar to the master mark of Thomas Stoer, the Elder,

Nuremberg, active 1597-1611 (Rosenberg 3/4081) The TS and the eagle

mark are in Scheffler No. 454 and 456

|

|

|

|

Basket by Neresheimer

|

Marks on basket on the left, only the

third mark is listed in Scheffler, No.517

|

|

|

|

Chased platter by Neresheimer, 45 x 60 cm

|

Marks on platter on the left – a typical

punch combination

|

|

|

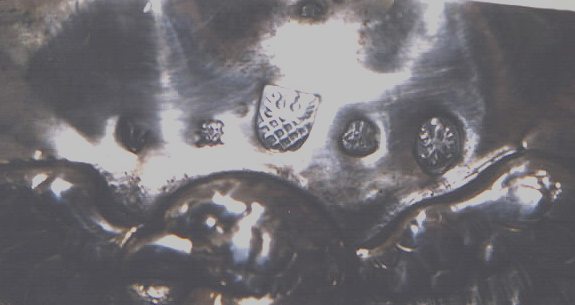

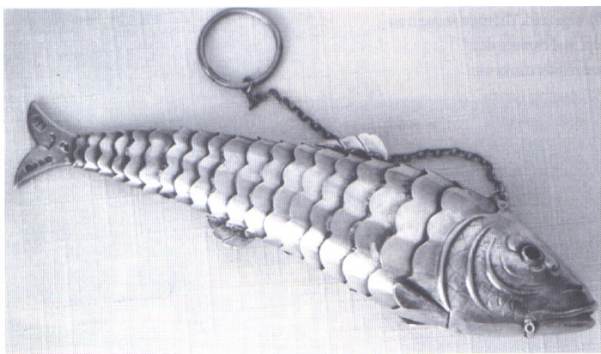

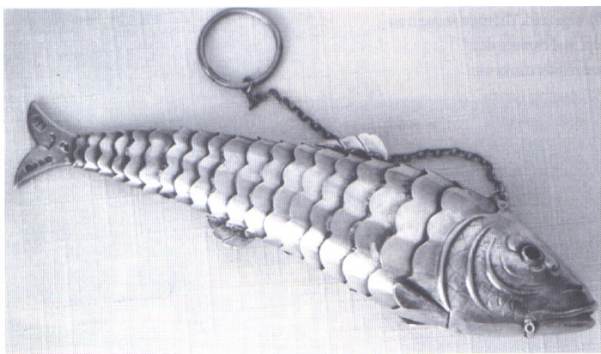

Fish-shaped box, by Neresheimer.

It has Chester, England import marks for 1903 and date letter C,

stamped twice once on the head, once on the tail, which also has a

BM mark for the importer Berthold Mueller

|

Neresheimer standing cup and cover with

Austrian import marks (not shown)

|

|

|

Neo-gothic beaker cup and cover by Georg Roth. The beaker is a

faithful copy of old German silver

|

the neo-gothic beaket cup has

French-looking marks and Chester, England import marks for 1900

|

Part 1 of this article is available

clicking here

Dorothea Burstyn - 2004

this article was published in Silver Magazine Nov./Dec.1997 -

reproduction on ASCAS website is authorized by the Author and the Editor

of Silver Magazine

|