by Maria

Entrup-Henemann

|

(click on images to enlarge)

LONDON SALTS OF THE 18TH CENTURY

Through my interest for the fascinating material "salt" I

became aware of the marvellous containers which were created to

keep and present this precious substance in ancient times. I

admired the great medieval salts which had not only a practical

use but, above all, a ceremonial importance, indicating the

relative status of persons by their position at the table in

relation to the large salt. However this use was not very

convenient, so that, at the end of the 17th century, so called

trencher salts were added. Trenchers were individual slabs of

hard bread or wood that served as individual plates. Finally the

large salts disappeared and individual salts were placed next to

each individual trencher or between two of them.

The trencher salts are the early type of salt cellars. There

were no spoons in use: you had to put the salt with your knife (as

long as it was clean) on the rim of the plate. The salts had no

feet and show a wide range of shapes: round, oval rectangular,

triangular or octagonal.

The trencher salts on the pictures below are my earliest ones.

They show an oval plan form with spreading bodies and dished

wells. They were made using Britannia standard silver (958/000)

in London in 1714 by the silversmith William Looker.

Dimensions: 8 / 6 / 3 cm, the combined weight is 112 g.

The Britannia standard silver was introduced in 1696 by

the British government as part of the great recoinage scheme of

William II in the attempt to limit the clipping and melting of

sterling silver coinage. It was thought that requiring a higher

standard on silver manufacture, people would be discouraged to

put in the melting pot the newly issued sterling coins. The lion

passant hallmark was replaced with the figure of a woman called

Britannia and the leopard's head mark for London was

replaced with a "lion's head erased". From June 1720

silversmiths were allowed to use again the sterling silver standard in

their manufacture.

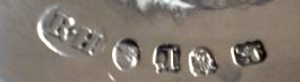

The trencher salts in the pictures below were made just after

this date. In this case, we have a pair of rectangular salts in

cut cornered style, bearing the date letter for 1721 and,

probably, the maker's mark GR, belonging to Gundry Roode (Grimwade

880).

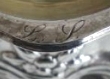

They measure 8,0 / 6,2 / 3,2 cm, weigh together 105 g, and have

monograms: EK on one salt and WL over EK on the other one,

possibly a wedding-gift.

Around 1730 the salt-cellars developed from plain

functional trencher salts to a variety of forms. First were

circular bowls on a collet foot and the more popular form with a

circular body on three or four feet. But salt is silver’s worst

enemy. Therefore, the inner surfaces were gilded or got a glass

liner. Many salts are nearly plain, but most of the fine

examples have rococo design: floral swags, lion masks above the

feet, shells, mermaids and so on.

The pictures below show three plain cauldron salts, made in 1738

by Edward Wood and in 1743 and 1748 by David Hennell I

(left) 6,5 x 3,25 cm, 60 g

(center) 6,4 x 3,5 cm, 45 g

(right) 6,4 x 3,8 cm, 60 g (without

glass, liner probably added later)

Edward Wood was apprenticed to James Roode in 1715, became free

1722 and entered his own mark. We find Wood in the line of

specialist salt cellar makers like his master Roode. In 1728

Wood became master of the young David Hennell, who probably made

more saltcellars in the mid eighteenth century than any other

silversmith.

David Hennell I (1712 - 1785) was – as above mentioned –

apprenticed to Edward Wood in 1728, became free 1735 and entered

his first mark 1736. He was the founder of the

Hennell-Silversmith-Dynasty. He had 15 children. Only five of

them achieved maturity. One of them, Robert, was apprenticed to

his father in 1756 (see below).

We go back to Edward Wood.

Below is illustrated a larger pair, made in 1749, 7 x 4,5 cm,

weighing together 180 g.

They have gadrooned borders, hoof feet with shell knees and

liners (probably added later).

The following pictures show two Cauldron salts with

rococo design: 1738 Edward Wood and 1746 TB (?)

This couple is not really a pair, probably the one of 1746 was

made to accompany the first one.

Both have a shield with a worn or partially removed crest.

The spoons (not sterling but EPNS later addition) have another

crest.

(left) 6,9 x 3,7 cm, 62 g

(right) 6,9 x 3,7 cm, 54 g

The next pictures show a pair of real master salt cellars, made

in 1748 by Daniel Piers.

They measure 8,7 x 4,3 cm, weigh together 270 g (!). They have

an elegant rococo design and an all over engraved C-scroll motif.

Everted, standing gadroon edges. On cast, tripod base with shell

knees and spread hoof feet. Interior gold wash. Each has a

shield with a well detailed crest.

There is no record of apprenticeship or freedom for

Daniel Piers and the first mark was entered in 1746. His work,

though comparatively rare, shows distinction of rococo design

and execution. It is believed that he was probably of Huguenot

extraction.

The following pictures lead us again to David Hennell I with a

pair of large master salts, made in 1752. They measure 8,2 x 5

cm, weigh together 320 g (!) and are decorated with embossed

floral swags and lion masks above the feet.

But times and styles changed. During the Adam period blue

glass liners became general, combined with a pierced design.

Meanwhile James Watt invented the steam engine and

industrialization began. Machine-rolled sheet-silver became

available, saving material because the sheets were very thin.

This advantage influenced not only the design, but also the

price of the salt cellars: they became less expensive. Hester

Bateman was one of the first silversmiths who used this method.

The most popular designs were a circular bowl on a spreading

base or an oval bowl on four feet. The decoration is generally

classical in inspiration, but free floral arabesques are found,

too. Among the designs, which did not involve pierced works, was

one with a boat-shaped bowl, with or without handles, on an oval

base.

The pictures below show a pair of salts, made in 1774 by Robert

Hennell I. They are 8,0 x 6,2 x 5,5 cm, weigh together 130 g (without

glass). One of the glass liners seems not to be the original one.

Robert Hennell I, (1741 - 1811) was the fifth child of

David Hennell I, apprenticed to his father in 1756, free in

1763. The first mark was entered in 1763 in partnership with his

father. A mark alone as smallworker was entered in 1772.

In 1773 he is listed as plateworker and a new mark was

entered as saltmaker.

The next pictures show a pair of salts, made in 1790 by Hester

Bateman, 8,9 x 6,3 x 5,4 cm, weighing together 90 g (without glass).

One of the glass liners seems not to be the original one.

The salts are lovely pierced and engraved and have a shield with

a monogram.

Hester Bateman (1708-1794) was married with John Bateman,

a chainmarker. He died in 1760 leaving all his property

to his wife who entered her first mark in 1761. She had five

children and was the founder of the Bateman-Silversmith-Dynasty.

She retired in 1790 when her sons Peter and Jonathan entered

their own mark.

The next items lead us again to the Hennells.

Below are pictures of a pair of boat shaped salts, made in 1792

by Robert Hennell I, max 14,8 x 5,8 x 8,8 cm, weighing together

190 g. The salts are of elongated shape with elegant loop

handles. Both bear an engraved monogram.

The presented items illustrate the history and the style

changes of salt cellars during the 18th century in London.

I would like to conclude my presentation with a further example

of an 18th century salt, not from London but from Augsburg (Germany).

The shape is a little different from those of London. But this

was a shape quite popular in Continental Europe, from Copenhagen

to Naples.

The pictures below show a pair of salts made between 1773 and

1775 in Augsburg (Germany) by Carl Samuel Betkober, 8,5 x 7,5 x

4,5 cm, weigh, together, 145 g, monogram L.S.

Any suggestion, correction or addition will be welcome.

|

Maria Entrup-Henemann

- 2010 -

|

|

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER