by Dorothea

Burstyn ©

|

(click on photos to enlarge)ALL THESE

NUMBERS....

In 'The Berry Silver Flatware Pattern by Whiting'

(note 1) William P. Hood, Jr. at a1. pointed

to Whiting's mysterious numbering system for flatware

pieces.

This gave me pause to think about all kinds of numbers,

found on flat- and hollowware. Most collectors are

familiar with termini technici like scratch weight,

British registration mark, etc. but in conversations

about the various meanings of all these numbers, I found

out that knowledge about these is sketchy at best. An

article giving more info about all these numbers seemed

like a good idea.

|

|

Let's start with the 'easy ones'. Fig. 1 shows the lid

and rim of a sauce tureen, bearing the numbers 4, thus

indicating that lid fits to body, but also that this

tureen was one of a set of four. Due to the common and

unfortunate practice of splitting up table and flatware

services at auction sales or between family members, 'pairs'

with the numbers 3 and 4 might be offered. A 'pair' with

the numbers 1 and 2 might be a true pair or the first

ones in a series of a larger number of items. Wine

coolers and soup tureens and their liners are often such

numbered, with the proper way of assembly (after

cleaning) in mind. |

|

|

fig.1: Mid Victorian Sauce Tureen lid and body are

both marked 4

|

|

Fig.2 shows a beautiful entrée dish by Mortimer and Hunt,

London 1843, the lid does not quite fit and the numbers

on body and lid '1 and 4' tell the rest of the story. It

might have been the butler, who in one inattentive

moment after cleaning managed to 'destroy' right away

two pieces of the service.

Numbering was also a common practice for Scottish

flatware pieces. Toddy ladles were usually made in sets

of half a dozen and are often found with numbers 1- 6

stamped in. |

fig.2: Mortimer & Hunt Entrée Dish on Lid. London

1843, here numbers do not match

|

|

Fig. 3 shows quite rare egg spoons, made ca. 1820 by

Alexander Cameron in Dundee. They are a 'set' of 6. The

fact, that they are numbered with 13, 14, 18, 20, 21 and

22 proves that there must have been 24 or more at one

time. An unexplained mystery is the number ' 34 ',

stamped on only one spoon, next to the monogram on a set

of 6 German spoons, all monogrammed with T. v. W. and

dating to ca. 1750. Fig. 4.

|

|

|

Fig.3: Two egg spoons made by A. Cameron, Dundee,

stamped with 21 and 20

|

Fig.4: 34 stamped on only one

spoon of a set of 6 German spoons, ca. 1750

|

Larger collections with multiples of the same items

introduced inventory numbers. This practice was amply

illustrated in the Thurn and Taxis Collection.

(note 2) Two different systems have been used:

A- Consecutive numbers for multiples of the same items,

like for example Lot 87, 'A set of six German silver

meat dishes, J.C. Drentwett I, Augsburg 1755-5' is

numbered with the inventory number 1 - 6,

Lot 121: 'A set of eight German silver table

candlesticks, Daniel Schaeffler I, Augsburg, apparently

1712-15, one lacking inventory number, the others: 77,

78, 79, 81 to 84, also engraved with scratch weights.'

Consecutive numbers were also used for ice pails, set of

salts, casters, etc. |

B-

Inventory numbers with two parts were used for sets of

plates and flatware, as for example in Lot 98 'A set of

twelve German Silver Dinner plates, J. C. Drentwett I,

Augsburg 1755-57' is numbered with 33-1 to 33-12. Fig.5.

Lot 84 'A German silver-gilt dessert service, Johann

Beckert V, Augsburg 1757 '59' consisting of forty-two

dessert spoons, forty-two dessert forks and forty-two

dessert knives with silver blades and are stamped with

inventory numbers: 9-1 to 12, 10-1 to 12, 11-1 to 12 and

12-1 to 6.

(note 3)

|

|

|

fig.5: Mid 18th Century plate # 33 - 6

|

Many but by far not all early silver pieces have weights

scratched in underneath. Fig.6. Scratch weights on

flatware pieces are rare. Fig.7. To understand scratch

weights and to correctly convert them to today's weights

is of utmost importance for the collector. Deviations

from the scratch weight are indicators for alterations:

A conversion from a teapot into a (much higher prized)

tea caddy by removing the spout and handle, conversion

from a larger mug to a teapot, added borders, spouts,

handles: the examples are endless. Additions on English

silver pieces are of course marked with contemporary

hallmarks, but sometimes one has to really look hard for

these in elaborate borders and handles. The English

system of scratch weights is straightforward. Troy

weight is used.

1 pound (lb) = 12 ounces = 373.2 grams

1 ounce (oz) = 20 dwts = 31.103 grams

1 pennyweight (dwt) = 24 grains = 1.555 grams

|

|

|

Fig.6: Mazarin, 1776 London, 28 oz. 13 dwt.

|

Fig.7: Strainer spoon, London

1774, 3 oz. 18 dwt.

|

American silversmiths adopted the English system. Fig. 8

shows the scratch weights on a silver brazier, made by

Myer Myers, New York, ca. 1755.

(note 4)

The weights for 18th century French silver are as

follows:

1 livre = 2 marcs = 489.506 grams

1 marc = 8 onces = 244.753 grams

1 once =8 gros = 30.594 grams

1 gros = 3 deniers = 3.824 grams

1 denier = 24 grains = 1.275 grams

1 grain = 0.053 grams |

|

|

fig.8: Myer Myers Brazier

|

French 18th century dinner plates of larger services are

stamped with consecutive inventory numbers, combined

with the scratch weights in marcs and onces.

(note 5) On March 28, 1812 the marc @ 250 grams

became the legal weight in France. In Switzerland the

weights mostly correspond to the French weights, with

three exceptions Zurich, Schwitz and Glaris used the

mark @ 234.9 grams. In Spain the mark weighed 230 grams

with small differences between various towns, Catalonia

268.35 grams and Navarre 244.6 grams. In Riga the mark

weighed 209 grams, in Vilnius only 194.8 grams

(note 6)

Most of the German lands used the Cologne mark.

(note 7) The Cologne mark converts to:

1 Pfund (lb) = 2 Marks = 467.71 grams

1 Mark = 8 Unzen = 233.856 grams

1 Unze = 2 Lot = 29.232 grams

1 Lot = 4 Quentchen = 14.616 grams

1 Quentchen = 4 Pfennig = 3.654 gram

1 Pfennig = 1/16 Lot = 0.9135 grams

1 Gran = 1/18 Lot = 0.812 grams

Fig. 9. shows the scratch weight, in German: 22 m[ark]//7

L[o]th, on La Machine d'Argent by Francoise Thomas

Germain for the Court of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

(note 8) |

|

Fig.9: 22 Mark //7 Loth on La Machine d'Argent

|

As mentioned before, the Cologne standard was not used

everywhere. There are many exceptions, all given in

Fabian Stein's article, to mention a few: Augsburg = 1

mark = 236 grams, Nuremberg = 239 grams, Prague and

Bohemia = 239,1 grams, Vienna/Bozen and Tyrolia - 1

Viennese mark = 16 lot = 280.644 grams. Divergences in

weights plus the fact that various materials were

weighed with different weights (troy for precious

materials, avoirdupois for others) makes us appreciate

the easy metric system so much more.

Even though manufacturer's numbers are usually

associated with more 'modern' silver - used from about

the middle of the 19th century - an early predecessor

existed. Many, but not all, Storr silver pieces have

three-digit numbers stamped in, which could not have

been inventory numbers. N.M. Penzer calls these 'order

number of Storr & Mortimer'

(note 9), 'pattern number or job number'

(note 10) is probably a more apt description.

Variations and inconsistencies are many, for example

only three of a set of 4 wine coolers are stamped 887, a

dinner service made for Sir Thomas Picton, 1814, is

marked 167 on 2 meat dishes and covers, a large meat

dish, two rectangular dishes and covers. Yet the

matching soup tureen and stand is not marked with this

number.

(note 11) The manufacturer's numbers is a logical

further development, but now every item was given its

own specific number. Note Fig.10 casters and salts, made

London 1867/68 by Hunt and Roskell in the 'Ashburnham'

pattern, the salts are stamped with 4801, the matching

casters with 4671.

An assembled Victorian tea set, London 1840/41 features

stamped-in manufacturer's numbers - 2055 for the sugar

bowl and 2074 for the milk jug, both pieces made by

Charles Gordon, but the matching teapot, made by Francis

Dexter has no number. Fig. 11. The obvious deduction is

therefore that around middle of the 19th century not

every silversmith used manufacturer's numbers, but by

1880 manufacturer's numbers were fairly common.

|

|

|

Fig.10: Hunt & Roskell Ashburnham Salt, # 4801, 1867

|

Fig.11: Charles Gordon Sugar

Bowl, 1850/1 # 2055

|

|

These numbers corresponded to order number in catalogues

or salesmen books as well as to numbers on cast moulds

and chucks.

(note 12) In American silver, the production of the

Gorham Manufacturing Company is best researched. The

John Hay Library in Providence, RI is the home of the

Gorham archives. Given the manufacturer's number, Samuel

J. Hough

(note 13) will research your Gorham silver item.

Gorham flatware patterns, as a rule, are designated

either by name or by number, but not both. However,

there are exceptions. For example, Gorham gave a

not-full-line pattern or grouping a name and then

designated different designs within that group by a

specific number. Flatware pieces with manufacturer's

numbers within a rectangle are special orders.

(note 14) Fig.12. |

|

|

fig.12: Toasting Fork Special Order # 1357

|

Tiffany flatware has generally two numbers: the first is

the pattern number; the second is the chronological

order number. Occasionally there is a third number,

representing a decoration design number. An example of

this kind of numbering is found on handmade Tiffany Lap

Over Edge dessert forks and spoons, on the back of the

spoon stamped with 356=pattern number, 1089=decoration

number and 3579=order number.

(note 15)

On English flatware pieces, yet another number with

different meaning is found. In Fig.13 a pair of

Victorian salt spoons with a journeyman's marks in the

form of the number '7' is shown. While most journeymen's

marks are symbols, numbers were also used. A journeyman

was a qualified craftsman who worked for a master. In

order to have a count of how many pieces a specific

craftsman had produced, a symbol or number was assigned

to him. The journeyman's mark may also have been a

method for quality control of produced pieces. It was

usually stamped in next to the sponsor's mark. In larger

flatware services, pieces with different journeymen's

marks may be found. To date there is no research into

the identification of individual journeymen.

(note 16) |

|

Fig.13: Journeyman's Mark 7 on Salt Spoon

|

On American hollowware one can find two different types

of numbers. Numbers consisting of 1-2 digits and

appearing on the underside of jugs, tea-and coffee pots

are capacity indicators - showing the capacity of the

vessel in half pints. Coffee pots normally bear the

number 7, tea pots the number 6, hot water pots the

number 5. Coffee urns may also bear capacity numbers,

usually between 13 and 20 half pints. 3-4 digits numbers

on American silver and silver-plate are manufacturing

numbers, denoting a certain pattern and also specific

types of items. In this connection I received a very

interesting email from Judy Redfield, who writes;

- 'Manufacturer's numbers can be used by researchers

for a variety of purposes other than simply tying an

item to an original catalogue. For example, since there

were very few companies that actually manufactured

silverplated hollowware, sometimes the catalogue numbers

on pieces can indicate which manufacturing firm was the

original producer of an item that bears the mark of a

smaller firm. If one is studying smaller firms it is

often helpful to determine who their suppliers were. The

book 'Victorian Silverplated Hollowware', published in

1972, reprints some old silverplate catalogues. One

catalogue it shows is Rogers Brothers Mfg. Co., for

1857. One might assume that the items shown in this

catalogue were originally manufactured by Rogers

Brothers, but certainly many, if not all, were not. They

were simply 'bought in the metal' and plated by that

firm.

For example, on page 29 of the book is shown a tea

service No. 1780. On the following page in the same

pattern is the matching coffee urn, and on the page

after that the matching water kettle. These pieces were

actually originally manufactured by Reed and Barton, not

by Rogers Brothers at all. How do I know? Because I have

the same pieces with the same catalogue numbers but

bearing the mark of Bancroft Redfield & Rice, a

contemporary of this particular Rogers Brothers firm.

One of my pieces, in addition to the number 1780, also

bears the mark of Reed & Barton. Both Rogers Brothers

and Bancroft, Redfield & Rice obtained some of their

wares from that source. Using catalogue numbers has

helped me to demonstrate a variety of other suppliers

for the Redfield companies as well. Besides if one looks

at all the tea service items in this Rogers Brothers

catalogue, one sees that the manufacturing numbers on

them are all in the 1700s. In addition to illustrating

the point about series numbering, this fact suggests

that the remaining tea service items in this Rogers

Brothers catalogue were also probably originally from

Reed & Barton as well.' -

(note 17)

To know manufacturing numbers of items has another

practical application for the collector. In their

chapter 'Fakes, Mistakes and Mysteries' in 'Figural

Napkin Rings', 1996, Gottschalk and Whitson point out

how manufacturing numbers can be used to verify the

authenticity (or lack of it) for certain items.

Gottschalk and Whitson illustrate how a variety of items,

such as toothpick holders, vases and card stands have at

times been 're-worked' to make them appear to be napkin

rings, due to the collecting popularity of the latter.

The manufacturing numbers on the pieces, when compared

to catalogues, indicate the item's true original

function.

(note 18)

The mid 19th century saw a tremendous increase in

manufacturing firms; international exhibitions promoted

trade but must have been also fertile hunting grounds

for trades people who were out to copy successful models

of other companies rather than developing their own. The

need for some protection was acute and the patent laws

catered to this. Registered patents were protected from

piracy for a period of three years. English silver shows

registration marks and numbers in addition to hallmarks,

- just for completeness it should be mentioned that

foreign companies or their agents also could register a

patent, so not all items with British registry marks are

necessarily of British manufacture. See Fig. 14.

The letters for the months are in both periods the same:

A = December, B = October, C or O = January, D =

September, E = May, G = February (and March 1st - 6th

1878), H = April, I = July, K = November (and December

1860), M = June, R = August (and Sept.1-19th 1857), W =

March.

Roman numerals are used to designate materials: I for

metal, II for wood, III for glass and IV for ceramics,

etc. |

|

1842 - 1867

|

1868 - 1883

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 14:registry

mark used between

1842 - 1867 |

Fig.14: registry mark used

between

1868 - 1883

|

|

YEAR |

LETTER |

MONTH

|

LETTER |

YEAR |

LETTER |

MONTH

|

LETTER |

|

1842 |

X |

January

|

C |

1868 |

X |

January

|

C |

|

1843 |

H |

February

|

G |

1869 |

H |

February

|

G |

|

1844 |

C |

March

|

W |

1870 |

C |

March

|

W |

|

1845 |

A |

April

|

H |

1871 |

A |

April

|

H |

|

1846 |

I |

May

|

E |

1872 |

I |

May

|

E |

|

1847 |

F |

June

|

M |

1873 |

F |

June

|

M |

|

1848 |

U |

July

|

I |

1874 |

U |

July

|

I |

|

1849 |

S |

August

|

R |

1875 |

S |

August

|

R |

|

1850 |

V |

September

|

D |

1876 |

V |

September

|

D |

|

1851 |

P |

October

|

B |

1877 |

P |

October

|

B |

|

1852 |

D |

November

|

K |

1878 |

D |

November

|

K |

|

1853 |

Y |

December

|

A |

1879 |

Y |

December

|

A |

|

Fig.15 shows the marks of a wine jug which patent can be

dated to October 28, 1875, it is hallmarked for 1878,

therefore within the protected period for the patent.

Even if the patent was long expired, the registration

number was often stamped in, see Fig. 16, the patent No.

5518 for a clever mechanism, whereby the moving of the

handle causes the lid to open or close is found on two

nearly identical jam jars, one marked for London 1898,

by Heath & Middleton, the other marked Birmingham 1929

by Mappin and Webb. |

|

|

Fig.5: Patent registration mark on wine jug, for

October 28, 1875, next to manufacturers mark of 2661 D

|

Fig.6: Mechanism for closing

and opening a jar, stamped with British patent

registration No. 5518

|

|

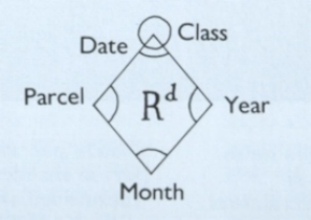

From January 1884 registered designs were numbered

consecutively and these numbers appear on wares with the

prefix 'Rd' or 'Rd No.' Fig. 17.

(note 19) Both English and American patents can be

searched on the net. A warning, it is a long and

time-consuming process.

(note 20) Judy Redfield is doing enormous research

into American silver-related patents and last time I

heard from her, she had things recorded to the middle of

1907.

(note 21) It is to be hoped that once finished, she

will publish the results of her research. |

|

|

fig.17: British Patent registration No. 189088 for

1892 on a small pickle fork dated 1893/4

|

|

Probably inspired by the financial success of limited

edition lithographs, modern silver companies started to

offer limited edition pieces. Apart from the more

pedestrian offerings like reproductions of vintage cars,

wall plaques for Christmas, Norman Rockwell scene

plates, etc - which can be seen regularly on Ebay - it

is to mention that serious silversmiths like Stuart

Devlin also participated in this fad. He produced

various silver eggs in limited editions of 100, 300 and

500, modelled on Faberge eggs - a nice-looking egg with

a surprise inside: there are the 1975 Easter egg, the

1980 Silver Jack in the Box egg, the 9 Ladies Dancing

egg to name just a few of his many limited edition

items. Fig.18 shows a London 1979 egg, stamped 259 500. |

|

Fig.18: Limited edition number 259/500 on decorative

egg, London 1979

|

|

In closing I want to mention a set of numbers, you do

not want to find on your silver - hastily scratched in

numbers - are often referred to as repair numbers and

were scratched in by silver repair shops in order not to

mix up repair jobs. There is a grey area though, since

some collectors thought they were inventory numbers for

retailers or maybe pawnbroker's marks. |

Dorothea Burstyn - 2005 -

photos by Douglas Hawkes

this is an article published on 2005 issue of the

'Journal' of the Silver Society of Canada

|

|

|

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER