by Dorothea

Burstyn

(click on photos to enlarge image)

TOASTING FORKS

The majority of toasting forks were made of iron,

brass or simple wire, this study only concerns

itself with the use, styles and history of the

silver toasting fork. It has been suggested that the

silver toasting fork was intended to be used in the

dining room "to give employment to amateur cooks"(note

1) or was handled "by those who preferred

to do their own toasting before the dining room or

sitting room fire"(note

2). These quotes seem to suggest that the

choice of material - silver - was determined by the

location in which this implement was to be used. In

contrast, modern thought categorizes the silver

toasting fork as kitchenware

(note 3).

The incentive to choose silver for so many medical

and kitchenware utensils must be found in the

hygienic properties of silver. Besides until the

mid-nineteenth century (and possibly even later),

people who could afford silver toasting forks had

servants who did all the food preparation.

|

|

|

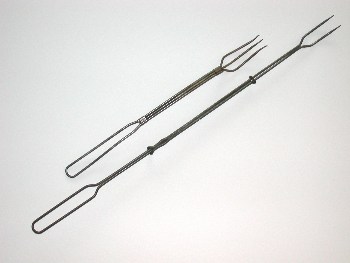

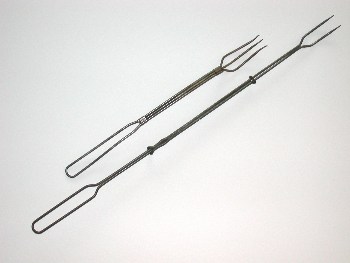

American kitchen toasting forks, made from

wire

|

Apart from the examples of toasting forks in my own

collection, which triggered my interest in the first place, I

wanted to make a survey of existing toasting forks. Looking

through auction house catalogues brought a few results, but a

search through the published catalogues of American museums

proved futile. The biggest collection of toasting forks (eleven

pieces) is in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. If one

wanted to enter into any meaningful discussion of style and its

evolution, a visit seemed imperative

(note 4). Most

of the V & A collection, which spans from 1669 to 1889, was

assembled with an eye for quality and the unusual by Dr. Louis

Clarke, a member of the Society of Antiquarians and curator of

the Fitzwilliam Museum

(note 5).The earliest example in the V & A, dated 1669,

as well as a Charles II silver-mounted toasting fork

(note 6)

feature elongated two-pronged forks with a backward hook,

devised so that slices of bread and cheese or meat could be

toasted together.

|

Two Charles II silver-mounted toasting forks,

ca. 1670,

Photo courtesy of Christie's South Kensington,

London, September 2001

|

Another Charles II fork has four prongs, more

suitable for toasting teacakes or apples. Both of

these Charles II examples are marked with DL, a

trefoil above and a mullet below, the mark of a

maker who might have specialized in these implements,

as he is also recorded in Jackson, revised, to have

made a "long toasting fork," 1672-73

(note 7).

Both examples have tapered handles with central

silver ferrules, the terminals furnished with reeded

ball finials and suspension rings.

|

|

|

Detail of Charles II silver toasting fork

|

|

Another toasting fork, dating to about 1680

(note 8)

and marked with the maker's mark of F.G over a star

in a shaped shield, features the same arrangement of

tapered handle, central ferrule and ball shaped

terminal with suspension ring, but is equipped with

a C-shaped, two-pronged fork with a pivoted

stirrup-shaped toast-holder. This fork combines the

toasting fork and a related utensil, the toaster.

The toaster has an arrangement of tapered back hooks

forming a basket-shaped device or rack in which a

sandwich can be inserted. A charming example is in

the V & A, dating to ca. 1690 and marked with the

maker's mark of Ro crowned. The toast holder

consists of two hooks, the ends of which are formed

as eagles' heads

(note 9).

The toaster with variations of basket and hook

arrangements is an enduring style. Examples found in

1709 (note

10) and Exeter, 1816 are on record. Another

more sophisticated specimen was made by Thomas

Whipham, London, 1749, the wirework basket being

attached to a short shaft via a hinge

(note 11).

T. Phipps and E. Robinson of London made a variety

of toasting forks and toasters

(note 12).

The pièce de resistance is an example dating to

1797: ingenious, yet simple, the triple-hooked toast

holder and a three-pronged fork are both hinged to a

tapering socket, the two hinges being arranged in a

way to allow either the toast holder or the fork to

be used. If the basket is used, the fork can be

folded parallel to the handle, a space in the hinge

of the basket holding it in place

(note 13).

|

George III silver toaster,

Exeter 1816, apparently

no master mark

|

|

From the 1790s on ingenuity was the name of the

game. A successful silversmith, Sir Edward Thomason,

reminisces in his Memoirs During Half a Century

about his inventions: "In 1809 I invented the

sliding toasting fork, some with one, two, or three

slides, within a handsome japanned handle, common

now in all the shops. I also invented one that by

the action of drawing the slide, the same movement

raised a shield from off the prongs, and upon

shutting up again of the slides this action moved

the shield over the prongs. I also invented a third

kind, which was that the three prongs collapsed

together, which, on the shutting up of the slides of

the fork, drew the same into the mouth of a snake,

the head of a silver snake being attached to one end

of the outer slide or handle. The above were made in

silver, gilt, plated, and brass; and large

quantities were sold even by me; but, as I did not

protect this invention by patent, thousands were

made and sold by other manufacturers"

(note 14).

An example of his wonderful toasting fork with

collapsible prongs, made of various metals with a

black japanned handle and a gold-plated snake head,

is in the collection of the Birmingham Assay Office.

Patented or not, the sliding - or better telescopic

- toasting fork was made much earlier than 1809 by

other makers, as there is an example marked with

maker's mark TID, dating to London, 1804, in my

collection and yet another one, made by the same

maker, 1807, in the former Albert collection

(note 15).

|

|

|

Toasting fork by E. Thomason.

Photo courtesy of

Birmingham Assay Office

|

|

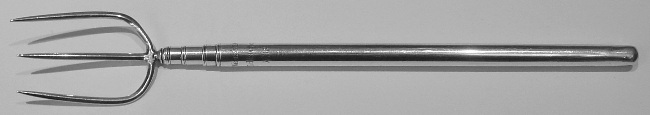

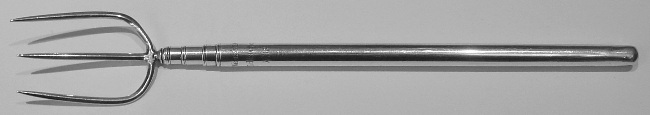

Telescopic toasting fork, London 1804, master

TID, with shagreen handle

|

A slender four-part extending toasting fork is hallmarked

for London 1809 and made by George Collins.

|

Telescopic toasting fork from Weeks Museum,

London 1809, by George Collins, fully extended.

Photo courtesy "The Finial" - Daniel Bexfield

Antiques, London Mayfair.

|

|

Detail of telescopic toasting fork, from

Weeks Museum, closed

|

It is inscribed around the outer collar with B[ough]t at

Week's R[oyal Mechanical] Museum, Tichbourne Stt, 1138.

Curiously a parasol with a telescopic handle and an inscription

identical to the one on the toasting fork (except for the number

1013) surfaced in the estate of a prominent English dealer. It

turns out the handles on both, the toasting fork and parasol,

are identical in length and were made by the same maker, but the

parasol handle was assayed in 1802. As Mr. Weeks started his

commercial life as an umbrella manufacturer, the question arises

whether both items started out as parasols or toasting forks

(note 16).

|

Telescopic toasting forks, supposedly invented

for traveling, are relatively short and measure

closed from 9 to 12 inches. They may have sterling,

Sheffield plate or japanned handles. The majority of

toasting forks are equipped with wooden handles.

Ebony or hard fruitwoods are most commonly chosen,

measuring 36 to 39 ½ inches; black buckhorn is seen

on Anglo-Indian toasting forks

(note 17).

I came across two all silver toasting forks, both

having handles very similar to Warwick cruet stands.

One is in the V & A (M.1674-1944) and is thought to

be a fake or a concoction of parts put together from

various sources. In any case, due to silver being an

excellent conductor, an all-silver toasting fork

without heat-spacers seems a very impractical

instrument.

|

Anglo-Indian toasting fork

|

|

Given the great variety of types, styles and patterns of

American flatware, it is surprising that not more American

silver toasting forks surfaced in the survey. Up to now I found

only two examples, one made by Gorham in 1889.

|

Special order toasting fork, Gorham 1889

|

|

Detail of the Gorham toasting form, note the

swivel mechanism

|

The costing record

(note 18)

calls it "1357 Toast Fork" and indicates that it was

a special order made December 4, 1889 for the

Providence, Rhode Island, retail jeweler Tilden &

Thurber. The three-pronged fork is attached via a

swivel to an extension rod that slides in and out of

the wooden handle and is controlled by a silver

screw on top of the socket. It measures 22 inches

closed and can be extended to a length of 36 inches.

The handle is fruitwood with a lovely acorn finial.

The central ferrule is divided into two parts by a

beaded band, the lower section being engraved with

M.P.B.H. Nov. 16th, 1889. That the inscription

features four initials (presumably his and hers),

plus the fact that the fork is engraved with a date

earlier than it was actually produced, makes one

suspect that it was given as a wedding present as it

was an accepted custom to give wedding presents up

to one year after the joyous event. The other

American toasting fork was seen on Ebay; it is also

made by Gorham, dating to the 1890s, featuring an

ivory handle, two elaborately shaped wires form flat

grips to hold the toast.

|

|

|

Silver toaster by Gorham, ca.

1890

|

As described earlier, two- and four-pronged forks were made,

but the most enduring form over the centuries by far is the

three-pronged type.

|

Toasting fork and bread fork ny T. Bradbury &

Sons, Sheffield 1918 and 1894

|

And when a new serving implement for bread was introduced in

the 1880s, it was the three pronged style that prevailed.

|

Two bread forks, Sheffield 1898 and London

1897

|

It is interesting to note that James Dixon & Sons made an

electroplated nickel silver combined bread and toasting fork:

the short version to be used for bread, the utensil is equipped

with a separate extension rod which transforms it to a toasting

fork (note 19).

We know from old records that toasting forks existed as early as

the 1550s in noble English households

(note 20).

Astounding is that - probably English-made - silver toasting

forks were to be found in America as early as the mid-17th

century (note 21).

Toasting forks were part of the equipment affluent students took

to university; Lloyd Evans received one as a present from his

mother in 1669 (note

22) and John Courtenay donated his toaster, made 1706,

to his alma mater (note

23). Given that dinner was served quite late at the

universities, a cheese toast or a roasted apple might have been

welcome treats in between meals. As mentioned before, telescopic

toasting forks were popular on travels. Recounting her early

travels to the continent, Lady Caroline Capel called her

toasting fork a treasure which made many a bit of sour bread

more digestable (note

24).

The legendary collector, tastemaker and bon vivant William

Beckford owned three toasting forks that he took with him on his

various travels (note

25). An epitome of sheer luxury and elegance is his

unique gold toasting fork. Bought shortly before his journey to

Portugal, it is dated 1793, measures 38 3/4 inches in length and

features exquisite floral chasing on the baluster stem and three

fluted prongs (Fig. 15 and Fig. 16). The elongated ebony handle

is capped in gold and furnished with a gold ring. As usual the

combination of impeccable provenance, beauty of design, precious

material and extreme rarity is rewarded in the marketplace; this

piece was sold at Sotheby’s in April 1998 for the remarkable sum

of $134,500 (note 26).

|

William Beckford’s gold toasting fork, London

1793.

Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s New York, April 1998

|

|

Detail of the Beckford gold toasting fork

|

Dorothea Burstyn is the Editor of the Silver Society

of Canada Journal

and Administrator of SSC website

http://www.silversocietyofcanada.ca

- 2010 -

|

|

|

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER