ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVERASCAS

| article # 88 |

|

next |

previous |

(click on photos to enlarge image)RUSSIAN SILVER ASSAY MASTERS IN THE WESTERN PROVINCES

|

Beaker by the

silversmith Claes Peters, Nyen, 1696-1704. Nyen

belonged to the Swedish provinces in Russia, the

city became later, after tsar Peter the Great’s

victory, St Petersburg. Claes Peters was born in

Helsinki, trained in Tallinn, and left Nyen for

Helsinki.

|

| LOT (GERMANY) OR LOD (SWE/FINL) | EQUAL TO RUSSIAN ZOLOTNIKI | SILVER CONTENT |

| 13 | Fineness not allowed in Russia | 812,5 |

| 14 | 84 | 875 |

| 14 1/3 | 88 | 916 |

| 15 1/3 | 92 | 958 |

Sometimes one can see the sample of the proof master or the alderman (eldest brother, chairman) of the guild, a zigzag pattern as on an adder close to the other stamps on the bottom of the piece. The 17th and the 18th century was a golden era of Baltic silver art and the craft of corpus silver makers did indeed flourish in European tradition, although the styles and taste were a provincial interpretation of the continental.

But the craftsmanship and the finish are of admirable standard.

From early beginning of the 18th century the provinces came under Tsar Peter the Great and Russian sovereignty, but his west oriented taste for craftsmanship was not strictly russified, although he moved citizens and skilled people by force to St Petersburg.

The regime for silver stamping and hallmarking continued under supervision of the guilds.

The russification of civil and economic life had started in the early 1800 in the Baltic provinces, unlike in Finland where the tsar had guaranteed the partial sovereignty of the country, its legislation and of the courts.

And in assaying silver. In the Baltic States this was not the case. By an administrative reform in 1842, the hallmarking and assaying was to be under the Russian rule and run from St Petersburg Mint.

At that time the first major Russian concentration and regulation of the Estonian silver craftsmanship supervision took place.

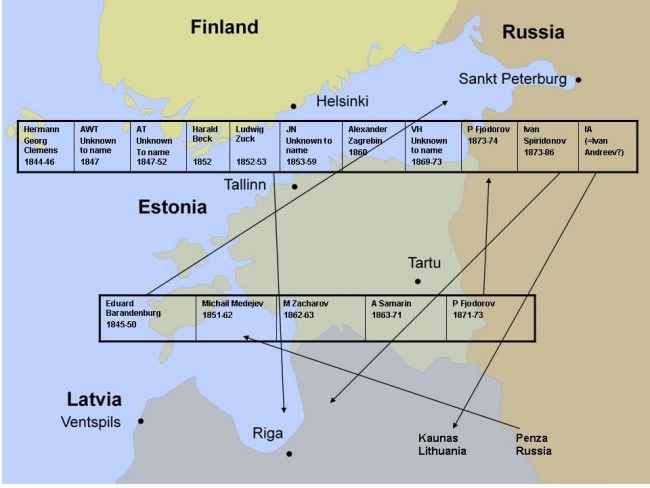

Map of Estonia

showing cities where silversmiths were

hallmarking up to mid 1800.

|

From that year up to 1873 they became the regional centres of Estonia. But, it was also possible for those silversmiths who lived in cities bordering to other assay stalls to go there for hallmarking.

It was possible to pass the border of the regions to have hallmarking made at your closest place.

And this causes a puzzle where to address the piece to its origin. From some Estonian cities the smiths went to St Petersburg or Riga.

We are now touching a general problem when it comes to Russian hallmarking. First, it was admitted to go to an assayer in another city, to the strongly regionalised hallmarking office to have your goods hallmarked. Of course this occurred very seldom, and the big workshops in Moscow and St Petersburg did no transport their silver unmarked to another city for stamping and sales.

Anyhow the law allowed this practise.

Town hallmarks of Tallinn after 1844, (three lions "en passant" or heraldically more correct, three leopards) |

This means that to address a stamped piece to its geographical location where it is produced, you have to know the smith’s identity and workshop location.

The next big reform in assaying came 1872, when another and even more radical concentration was decreed. Only four assaying centres were left in the eastern part of Russia, St Petersburg, Riga, Vilnius and Warsaw.

The assaying history of Estonia was closed and finished, and reappeared first after its independence 1918.

This regime became a radical centralisation and complications for provincial silversmiths. They had to go to the assay stall of a Guberniya, to get their hallmarks.

The hallmarking staff in St Petersburg was increased. A centralised stall was created in Riga to cover the provinces and the cities close to the coast.

Now we are closer to the solution of the fork puzzle.

Both silversmiths were active in Tallinn but the latter had regularly to go to St Petersburg with his silver to have it stamped before sale. The old one is made just before 1842 by Gottfied Erhard Dehio in Tallinn and is stamped with the Tallinn town mark of the cross, 13 Lod and the initials GD.

The second is by Leopold Eduard Michelsen, obviously stamped in St Petersburg 1894 but the assay master initials A Sh, which is Alexander Timofeevich Sheviakov.

The forks are both from the same city but manufactured with a wide time gap, over-bridging the imperial charter of 1842 and thus the latter is stamped in St Petersburg. It is probable that Leopold Michelsen took over the chasing forms for the forks from the Dehio family (they are known, father and son, to have run their workshop between 1810 and 1886).

The only difference between the forks, except master and time, is that the minimum silver content is 62/000 higher in the later one (13 lod versus 84 zolotniki).

Another piece of the Leopold Michelsen’s workshop in Tallinn, a ragout (serving) spoon hallmarked by Alexander Sheviakov 1890 in St Petersburg |

No, there is another thing to keep in mind. According to the assay charter not all corpus silver, jewellery and table services were stamped by the assayer with the full "triple" stamp, which means, from left to right, Assayers initials (with two characters) and under it the year, Silver content (most often 84 zolotniki) and Town mark. The minor "double" with smaller and more indistinct town mark was often used, and sometimes the town mark is mis-struck or not clearly visible.

And, up to about 1900, the assayers stamped with an individual stamp with their initials, thereafter only with the head assayers’ initials.

If the assayers’ initials are traceable on a piece but the town stamp is doubtful, can the mystery still be solved?

One complication is that Assay masters moved between assaying stalls, but recent research has made it possible to track their places of employment.

But why did they move?

The silversmiths were fairly immobile and stayed at their workshop for their lifetime, but why not the assay masters?

Maybe there are various explanations, but one is that in assay master’s career to become head of an assaying office was very attractive. And the qualifying years were to be spent in not one office only.

In the big cities in Russia, the head of an assayer stall was very well paid, so they would not be tempted to take bribes or look through the fingers when examining goods from their clients belonging to the same profession. The head assayer salary in St Petersburg was on the same scale as that of the highest officials at the tsar’s court.

The assay masters of Estonia were not an exception, some moved from Tartu to Tallinn and Riga, from Tallinn to Riga and St Petersburg. And what are the conclusions from this exercise?

Later research has opened sources which make it much easier to trace both silversmiths and assayers in the tsarist Russia.

Still, with the historically continuous concentration of the assay institutions in Russia, to exactly decide the place of origin, when is not immediately obvious, demands a methodology like that in a detective story. And, that is maybe what is a little thrilling for a silver collector.

Sources:

Backsbacka, L, Narvas och Nyens Guldsmeder, Helsinki 1949

Bukowski exhibition catalogue, Sverker Astroms silversamling,

Stockholm 1994

Ivanov A.N., Assaying and hallmarking in Russia (1700-1946),

Moscow 2002

Postnikova-Loseva, M. M. et al, Zolotoe i Serebrianoe Delo XV-XX

vv., St Petersburg 1968, edition 2003

Renans, Alur, Hobedamargid Eestis, Tallinn 2005

ENDNOTE

Guberniyas is to be translated as regional adminstrative unit.

Willand Ringborg © - 2007 - |