by R. T. H.

HALSEY - an article from Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 1 (January

1916)

(click on photos to enlarge image)

THE CLEARWATER COLLECTION OF COLONIAL SILVER

American Art -its expression by our painters, sculptors, and

craftsmen and the recognition of them by our people- was until

recent years handicapped by the belief that our art was of

recent growth and lacked the weight of history, tradition, and

inheritance, which in the minds of many seemed necessary for its

widespread recognition.

This erroneous belief is fast becoming dissipated, largely

owing to the development of collections of American decorative

art by the Metropolitan, Boston, and Providence museums. Their

examples are being followed by the managements of other museums,

notably the Brooklyn Institute and some of our large western

museums. By these collections they are demonstrating that

artistic sentiment has long existed here and played an important

part in the early social life of our people.

Colonial silver of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

in its perfection of form, texture, and craftsmanship may be

studied in the Clearwater Collection, now located in Gallery 22

on the second floor. All the pieces in this collection -the

result of years of patient gathering by Judge A. T. Clearwater-

were made in America, and with few exceptions are the work of

native-born Americans who had learned their trade in this

country. No student of American art and the development of

artistic taste in this country can fail to recognize the work

and influence of our early silversmiths, their artistic

conception and superb craftsmanship. Their handicraft is the

earliest expression we have of our forefathers’ appreciation of

the beautiful, an appreciation which became widespread as the

country prospered and furnished a steadily increasing patronage,

which encouraged a succession of craftsmen, whose works assisted

to beautify our American homes and today bear silent witness to

the artistic tastes and desires of many whose descendants now

people our great republic.

Half a century before the time when the first portrait

painter ventured to Boston (1701) -and was permitted to enter

only after giving bond "to Save the town Harmless"- silversmiths

prospered there, and one hundred years before Copley first gave

us his portraiture of our colonial aristocracy, many of the

communion tables of our churches were supplied with silver

vessels of local manufacture, whose charm and workmanship seem

impossible of reproduction today.

The methods of these early American silversmiths were far

removed from those of the craftsmen of the twentieth century:

often their work was done in their homes instead of in shops

with glittering showcases. They received from our ancestors coin

which had been brought in from the West Indies in payment for

the products of fisheries, forest, and farms; this after being

weighed and receipted for, was melted into ingots, hammered into

sheets, welded into various forms, and returned to the original

owner -upon payment of charges for fashioning- in the form of

vessels for use on the dining table, where they shimmered and

shone in sun-and-candle-and fire-light and thereby furnished the

first and only joyous note to the none too cozy atmosphere of

our early ancestral homes.

The equipment of a well-established

seventeenth-century English silversmith and the

processes of manufacture are well i llustrated in

the reproduction of an engraving which served as a

frontispiece for "A new Touchstone For Gold and

Silver Wares", published in London in 1679.

|

No art exhibition held in this city so instantly influenced

and directed an understanding of our early artistic

accomplishments as the Hudson-Fulton Exhibition held at the

Museum in 1909. It is not too much to say that it brought

prominently into the regular channels of commerce colonial and

Georgian art by making possible a widespread appreciation of it.

Queen Anne, Chippendale, Hepplewhite, and Sheraton pieces, which

had hitherto lurked in the windows of the antique shops of the

side streets, immediately appeared (and have since remained) in

the show windows of our palatial shops on the Avenue. Silver

plate of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century forms has since

decorated the showcases of our great silver shops. All

interested in American craftsmanship have noted the influence of

this exhibition upon our craftsmen who work in metal.

That same rare inspiration and opportunity for careful scrutiny

and study, hitherto given to our designers and decorators by the

Departments of Decorative Arts of the Museum and Cooper Union,

can now through the Clearwater Collection be supplied to those

who work in silver. The collection is of the period when ancient

geometrical shapes held sway among craftsmen; when purity of

form, sense of proportion, and perfection of line were preferred

to elaborateness of design; when dignity and solidity were

considered superior to bulk; and when the plain, polished

surface of the beautiful white metal was allowed to take its

color note from its surroundings rather than to serve as a

medium for the display of skill by craftsmen. Judge Clearwater’s

loan also includes a few pieces of our nineteenth-century plate,

which well illustrate the decadence of the art of the

silversmith during that atrocious period of craftsmanship known

as the Victorian Era.

The collection, which has been constantly added to, has just

been rearranged, and now for the first time it is easy for

students to study the chronological development of our early

styles and fashions. The work of each maker has been grouped,

thereby making it possible in many cases to identify the

personal touches in manufacture so peculiar to our early

craftsmen. The descriptive labels, which accompany each piece,

bear facsimile drawings of the maker’s mark, a feature not found

in previous exhibitions of old plate.

Pen and camera are inadequate to its proper description. The

subtleties of texture and light and shade baffle reproduction;

every piece of hollow ware has its own individuality of size,

form, texture, and color. The exactness and precision of the

stock pattern of today fortunately are lacking. Personality

predominates.

|

|

Cup by unknown maker

|

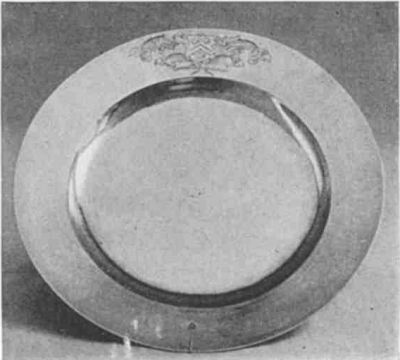

Plate by Samuel Minott

|

All the pieces are rare and many are unique; while in

general lines they follow the fashion and forms of old England,

certain of them show charming individuality of shape and

decorative motive not found in the plate made in Europe.

The collection contains over one hundred and forty beautiful

pieces of hollow ware. Its completeness enables an exhaustive

study of the chronological development of the various forms of

beakers, tankards, porringers, mugs, and teapots, and various

other articles used upon the table. Spoons, sugar tongs, etc.,

are to be found in great abundance. In fact, an exhaustive

catalogue of the collection would form a textbook of American

silver and its makers.

|

The collection is especially rich in the work of the

silversmiths who lived in Boston during the later part

of the seventeenth and the early years of the eighteenth

century. These have a greatly added interest in that

they are the work of men, all of whom took a prominent

part in the development of New England -its resources

and democracy.

The wondrous life stories of many of the makers of these

pieces of American silver have already been told in the

lengthy historical introductions of the catalogues of

loan exhibitions held in the Boston (1906) and

Metropolitan Museums (1911). Enough has already been

written to give us an insight into the histories,

personalities, and environment of these early colonial

craftsmen and to make these examples of their handiwork

very personal and almost human. It is not the purpose of

this article of appreciation of the results of Judge

Clearwater's collecting to retell these tales.

Probably to many the most fascinating piece in the

collection is a teapot of wonderful texture and color

made by John Coney (1655-1722) of Boston, who it will be

remembered engraved the plates for the first paper money

used in America. The coat of arms it bears testifies to

this early American engraver's skill with his engraving

tools. It is the earliest American teapot of which we

know. A tankard and a porringer by the same maker are

noteworthy pieces.

|

Teapot by John Coney (1655-1722)

|

|

Judge Clearwater has been extraordinarily fortunate

in securing four remarkable pieces bearing the mark of

Edward Winslow (1669-1753), also of Boston, whose work

entitles him to be recorded as the greatest of our

colonial silversmiths. He was an American, the grandson

of the John Winslow who came over in the Fortune in

1623, and on his mother's side was a direct descendant

of Anne Hutchinson -that goodly dame whose life figured

so largely in early New England and New York history.

Winslow, in common with almost all of our

early silversmiths, was very prominent in the civic life

of the community. He served successively as constable,

tithing-man, surveyor, overseer of the poor, selectman,

and sheriff of Suffolk County (1728-43); from this

office he was appointed Judge of the Inferior Court of

Common Pleas.

Defense in those days was not the neglected problem

it is today. In 1702 he was second lieutenant in the

artillery company and in 1714 its captain; he was major

of the Boston regiment in 1729 and its colonel in 1733.

The elaborately wrought chocolate pot and beautifully

fashioned plate illustrated herewith, and two tankards

demonstrate the very high order of his craftsmanship.

|

|

| |

Plate by Edward Winslow (1669-1753)

|

William Cowell (1682-1736) is represented by a porringer. It

is the same Cowell thus referred to by Samuel Sewall under date

of June 21,1707: "Billy Cowell’s shop is entered by the chimney

and a considerable quantity of plate was stolen. "

John Dixwell (1680-1725), the son of the "regicide, " Col.

John Dixwell, who found an asylum in America and lived in

retirement in New Haven, is another of these early

eighteenth-century silversmiths whose work may be viewed in the

collection.

John Burt (1691-1745) was the maker of the splendid brazier

illustrated below. Of equal interest is the work of his son

Benjamin Burt (1729-1804).

|

Brazier by John Burt (1691-1745)

|

The work of the Reveres, father and son, is also

well represented. The father, a Huguenot boy, served his

apprenticeship under Coney; the son, the patriot and

messenger of prerevolutionary days, was only nineteen

years old when his father died and left him to carry on

the trade which he had so successfully developed.

The exquisite teapot of the period of 1790, illustrated

on the right, has aesthetic qualities which demonstrate

Revere's artistic excellence.

|

|

| |

Teapot by Paul Revere (1735-1818)

|

|

Salem, Providence, Newport, and Philadelphia have

contributed to this splendid collection.

New York is adequately represented.

A splendid coffee pot of the middle of the eighteenth

century, fashioned by Pygan Adams of New London,

indicates that superb craftsmanship flourished outside

of the confines of our largest cities.

|

Coffee pot by Pygan Adams (1712-1776)

|

|

Undoubtedly, the most beautiful piece of New York silver in

the collection is a beaker made by some late seventeenth-century

Knickerbocker silversmith. Its makership cannot be identified,

however, owing to the partial obliteration of the maker’s mark.

It is a form greatly in vogue among our early New York

silversmiths, whose work as a rule followed closely the

conventional forms and decorations of the Dutch silversmiths.

This same Dutch influence is found in many examples of English

plate of the sixteenth century; in form and ornament, the beaker

closely resembles a London beaker bearing the date-letter of the

year 1599.

To all Americans who rejoice in the stories of our country’s

past -its ideals and its struggles to maintain them- and to all

jealously apprehensive of our country’s future -endangered by

isms and political nostrums- this ancient silver of Judge

Clearwater must have an added charm which no foreign plate can

possibly possess; for it represents the work and personalities

of men who gave to the country the best they possessed in the

form of service to church and state and thereby assisted in the

gradual moulding and welding together of the various integral

units of colonial life into the great republic of which we are

so proud and whose traditions we hold so dear.

|

|

|

|

Beaker, New York

17th century

|

Mug by John Dixwell

(1680-1725)

|

Chocolate pot

by Edward Winslow (1669-1753)

|

Mug by Kaiser Griselm

(late 17th century)

|

R. T. H. HALSEY

This article was firstly published in Metropolitan

Museum of Art Bulletin 1 (January 1916)

|

|

|

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER