by Fred

Sinfield ©

(click on photos to enlarge image)

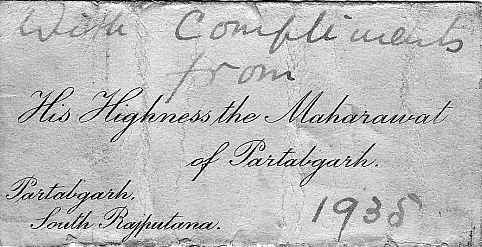

A PRESENTATION FROM HIS HIGHNESS

The gilded silver box contained a personal card

informing that the presentation was With Compliments

from His Highness the Maharawat of Partabgarh,

Partabgarh, South Rajputana 1935.

The presenter being His Highness Maharajadhiraj

Maharawat Shri Sir Ram Singh II Bahadur, KCSI, of the

Sisodhyia dynasty born in 1908, ascended to the throne

in 1929 and died in 1949.

on the right: A photograph of His Highness

Maharajadhiraj Maharawat Shri Sir Ram Singh II Bahadur

of Partabgarh, India, the patron and presenter of the

box featuring thewa work of the Raj Sonis in 1935.

|

|

|

The card in the silver box informs that it

was presented With Compliments from His Highness the

Maharawat of Partabgarh, Partabgarh, South Rajputana

1935, possibly to a an ex patriot Civil Service

officer for services rendered.

|

He was the ruler of the small princely state founded in 1433

as Sadri; renamed Partabgarh in 1698 then in 1818 became a

British protectorate and since 1948 part of the state of

Rajasthan, India.

The decoration of the box is different to other types of

embellishments used on box lids and is known as theva or thewa

work that is unique to Partabgarh in the Chittorgarh district of

India. There are differing stories of how this technique was

developed, one is that Nathu Soni invented the process but was

imprisoned when he refused to impart his secret to his ruler or

the goldsmith Nathuni Sonewalla developed the process in the

second quarter of the 18th century.

There is also another story that the technique originated in

Bengal about 400 hundred years ago where it was not received

well so the family of Bengali artisans set off in search of

patronage.

The Maharawat of Pratapgarh gave a land grant and his patronage

to these Hindu artisans so they settled in Rajasthan where they

taught male members of the Soni family, who call themselves 'Raj

Sonis’, the secrets of the craft that passed directly from

father to son over the generations.

The unmarked hinged lidded rectangular box presented by His

Highness depicts a scene of a prince mounted on his steed aiming

his rifle at a lunging big cat whilst another beast watches the

event, set on a green glass background within a cut out border

design.

The box measures 45x35x25mm, gilded externally and internally

and the sides embossed with a continuous floriated design within

a punched border.

|

|

The scene on the lid of the hinged lidded

rectangular box; showing a mounted prince aiming a

rifle at a lunging big cat set on a green glass

background within a cut out border design.

|

A close up of the gilded box with the sides

embossed with a continuous floriated design within a

punched border.

|

The presentation of this box was possibly to a Civil Service

officer connected with the "Allocation of Seats under the

Government of India Act, 1935, for the Upper Chamber of the

Federal Legislature for British India".

The other hinged lid container from the collection of and

illustrated in Dr. G. Cummins book is described as a Miniature

Eastern spice box in silver with gold overlaid green glass top.

The three small drawers in the base are probably for expensive

spices such as saffron.

The scene on the lid is set within the same border design as the

other box but features a seated female, a big cat, birds and

floriated designs. The hinged lid does not have a foil backing

used in other versions but relies on the reflection from the

shallow compartment beneath.

|

|

The oval hinged lid container from the

collection of Dr. G. Cummins features a seated

female, a big cat, birds and floriated designs

created using the thewa technique.

|

The lid of the oval box back-lighted showing

the details of the gold work on a green glass base.

|

The lid compartment or one of the three draws in the base

could be used to store sindoor, the vermillion paste used by

Indian women to indicate their marital status. In the base, the

central sliding draw is the full depth of the box whilst the

draws on either side in self-contained compartments about the

central draw and there is also a base rim.

|

In the base of the oval box is a full-length

draw whilst those on either side are in a

self-contained compartment possibly to hold spices

or cosmetics.

|

The solidly constructed oval silver container is 50x25x45mm,

weighs 56grams and is unmarked.

The workmanship on the lid of both pieces is similar but the

oval box has finer detailed gold work, which indicates that this

box predates the rectangular one by some decades. As it is

undated, it could be from the reign of either Udai Singh who was

the Maharawat from 1864 to 1890 or his successor Raghunath Singh

from 1890 to 1929. The former rather than the latter is favoured

due to the quality of the workmanship. The standard of thewa

work had declined by the time of the presentation in 1935 as the

weight of 36.4grams suggests and the finish lacks the fineness

of the oval box. The earlier, heavier and finer finished pieces

are more appealing as the artisans had the time to work on the

creation of each item.

Some of the finest examples of this unique form of decorative

art are in local museum collections in India as well as abroad

including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Victoria &

Albert.

Although not often seen on the market outside of India, one

thewa piece was for auction at Donnington Priory in July 2005.

This was A 19th century gold Partabgarh thewa-work necklace,

circa 1860-70, in the form of seven graduated oval green glass

panels inlaid in gold and depicting hunting scenes with horsemen,

and flowers and animals, mounted within alternate polished and

burr-bead borders and with a bell-shaped filigree and beaded

tassel fringe, to a two row woven cable-link back-chain on a

similar thewa-work panel clasp, in a fitted case from 'Phillips

Bros & Son, Art Goldsmiths, 23 Cockspur Street, London', approx.

46cm long overall (18 in). This was memento of Partabgarh,

possibly acquired by an ex patriot or visitor, who took it when

they returned to the UK and sold it to the goldsmith who boxed

it for resale.

The process of making thewa work is detailed; time consuming and

intricate, taking up to a month to complete each piece. It

starts with broken pieces of terracotta, finely ground, mixed

with chemicals and oil to produce a thick paste. The paste

spread on a wooden base has a 23carat gold sheet of 40gauge

thickness set onto the mixture and the free hand design etched

on it. Black paint spread over the gold sheet highlights the

design so it becomes clearly visible for further detailed work

with fine tools. The craftsman removes the excess gold creating

a design often based on Hindu mythology or Mughal court scenes,

historical events or with fauna and flora motifs.

Gentle heating enables the peeling of the gold sheet from the

base, which is a delicate step as the fragile sheet can break or

lose shape; then thoroughly washed and cleaned with a mild acid

solution. A piece of coloured glass traditionally red, green or

blue, acquired from windowpanes of old buildings, is cut to the

same size as the gold pattern and the silver frame and heated.

Pressed onto the surface of the glass while it is still hot are

the silver rim and the film of gold, by gently reheating the

metal and the glass fuse and then allowed to cool slowly. Often

fixed to the base of the glass is a thin piece of silver foil to

give a uniform lustre, which is then encased in a silver bezel

mount to finish the process. There are, however, limitations as

to size of these panels as there is the danger of large pieces

of glass cracking during heating. Over time the glass is liable

to crack as it is fragile when used for this purpose.

Prior independence in 1947, thewa craftsmen

relied on royal commissions but this patronage waned,

so post-independence there was little interest in

this type of luxury items. The practice and

knowledge of the art declined and languished due to

lack of demand but has since had a revival,

especially for jewellery pieces.

on the right: interest waned in thewa work after

Indian independence but has subsequently had a

revival as seen in this modern neck jewel using the

400 hundred-year-old technique

|

|

Ganpat Soni, a National Award winner and a modern master in

the technique of thewa said that … the work requires intricate

detailing and skilful fusion of the gold into the glass base,

the wastage is high. Overheating can break the glass or melt the

gold. Alternatively, if not treated properly the gold filigree

does not fuse well and soon comes off. The problems are many -

few selling outlets, lack of real appreciation for a thewa

piece, with people often questioning the purity of gold rather

than admiring the intricacy and skill of the designs. Also,

Belgian glass, the base material for a thewa piece is becoming

increasingly difficult to find and new sources are not

forthcoming.

There is increased awareness of thewa work as

Ganpat Soni received enthusiastic responses to

displays and demonstrations of the craft at

international fairs and exhibitions, but regretfully

he added - very few confirmed orders. The variety of

items made using this technique is large and

includes personal items, jewellery, plates, picture

frames, perfume bottles and vases.

on the right: there is increased awareness

internationally of thewa work but unlike other

precious metal items the value of a piece is the

skill and time required to fashion it as seen on the

lid of this modern revival box

|

|

Unlike other precious metal items, the value of a thewa

piece is not the intrinsic value but the skill required to

fashion the piece.

Further information is on various web sites that cover the story

of this unique art form of the Sonis of India.

Bibliography

Oppi Untracht. 1997. Traditional Jewelry of India. Thames

& Hudson. London.

Rita Devi Sharma & M Varadarajan, 2004. Handcrafted Indian

Enamel Jewellery. Roli & Janssen, New Delhi.

Dr. G Cummins. 2006. Antique Boxes Inside and Out.

Antique Collectors Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk.

Web site: www.craftrevival.org/Artisans/002594.htm

Fredric Sinfield © - 2007 -

|

|

|

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER