ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVERASCAS

| article # 90 |

|

next |

previous |

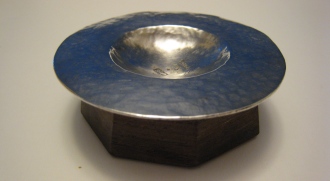

(click on photos to enlarge image)The World of Mexican Silver SaltsThe history of silver in Mexico combines both legend and fact. Taxco is the center - it is located between Acapulco and southwest of Mexico City in the hills. Before the Spanish arrived, the native Indians called it TLACHO meaning the place of the ballgame. According to local legend, the Aztecs had the locals pay tribute to them with gold bars. Cortes conquered the Aztecs in 1521 and then staked his mining claim in Taxco. By the end of that century, silver from Taxco had spread across Europe and Taxco, as a silver center was born. It became Spainís primary source of silver. As other mining areas in the world became more accessible to Spain, the interest in Taxco decreased and faded out for almost 200 years. In 1716, Don Jose de la Borda rediscovered silver in Taxco, when he was riding and wandering in the hills. He spotted a rich silver vein and turned that find into a fortune, rewarding the town by building schools, roads, houses, and the Santa Prisca cathedral. If you go to Taxco, the church can be seen from all over - it glitters in the sunlight. Donít ask me why he used so much gold when it was silver they were mining. Don Jose also built a private residence called Casa Borda which later became an essential workshop for silversmiths. During Mexicoís War for Independence in the 19th century, Spanish barons destroyed the silver mines instead of letting them go to the revolutionaries. So, again the art of silverwork died out again. In 1926, William Spratling, an architecture professor from Tulane University, decided to study Mexican culture and choose Taxco for his study. He spent three summers learning about the area before moving to Taxco in 1929. He met U.S. Ambassador Dwight Morrow in 1931, who commented to Mr. Spratling that Taxco had been the site of silver mines for centuries but had been left unknown in silver circles. Spratling changed all of that. He opened a shop (La Aduana) to pay his bills and living expenses and it showcased local talent of weavings, tin ware, copper and furniture. By 1933, the shopís biggest attraction was silver. Using the native rosewood, gold, copper, bronze and abalone he was able to create some incredible masterpieces. William Spratling taught many of the local citizens about the craft of silversmithing. He used an apprentice system which worked well. Zorritas were young men running errands and eventually grew in technical and aesthetic understanding to become maestros of their craft. As they became more experienced and skilled, he was able to open - Taller de las Delicias. As the number of employees grew, many were encouraged to open their own shops. It was important to Spratling to create a tradition where none had existed before. As his company expanded, he needed an infusion of money, so he brought in outside investors. This brought in money, but also new management, who didnít agree with Spratling. He resigned from his own company in July 1945 and went to work on personal designs. The U.S. Department of the Interior had talked to Spratling for several years about creating a format to train Alaskan students to design and fabricate silver jewelry, objects and sculpture based on traditional native designs and using indigenous materials. Spratling's plan was finally accepted and Spratling created 200 models for the project. Seven Alaskan students flew to Spratling's ranch in 1949, where for several months, each was trained in the methods that had proven so successful in Mexico. The students returned to Alaska. A lack of subsequent government support and funding brought rapid closure to this project. Spratling, however, after spending considerable time in Alaska as he researched the Alaskan and North West Coast heritage, came away with new ideas that dramatically influenced his later designs. Some of the first evidence of this new dimension to Spratling's designs appeared in those pieces marked "Spratling de Mexico". Those Spratling designs were produced at both the Conquistador factory in Mexico City and at Spratling's ranch during 1949 and 1950 (The arrangement with Conquistador was terminated in 1951.) Subsequent designs also carry on this more stylized, streamlined, refined line. The use of shallow, flowing, incised lines, and ebony, azurite, tortoise shell, yellow jasper, rosewood and malachite enhance the reflections, shadows and planes of the silver. Spratling also, during this period, produced ebony and gold jewelry designs. Spratling continued the use of applied silver circles, inset rosewood or ebony circles, stylized animals themes, and other design elements, but always in a simpler, sparer, more distinctive fashion. Throughout Spratling's career, he created custom work for clients. Spratling combined his interest in Pre-Columbian artifacts with his talents as a designer and produced some exceptional pieces of jewelry using Pre-Columbian jade in combination with gold beads. I was lucky enough to attend a Spratling exhibit in San Antonio, TX and see newly discovered objects that Spratling had made during his time in Alaska. William Spratling was killed in an automobile accident outside Taxco on August 7, 1967. His ranch, hallmarks, and all designs were purchased by Mr. Alberto Ulrich whose family continues to produce Spratling designs through the company Sucesores de William Spratling S.A. He is known as the "Father of Contemporary Mexican Silver". About the photographs

|

Linda Drew - 2007 - |