(click on photos to enlarge image)

LONDON HALLMARKING ON 19th CENTURY FLATWARE

The methods of marking from 1781 onwards require a good deal

of close examination to determine what nuances of difference

were introduced in the engraving of punches to outwit

unscrupulous silversmiths.

As I have stated elsewhere it becomes obvious that marks on

teaspoons could be easily "let in" on the foot rims of jugs and

other similar items so that it was of some importance that

teaspoon marks could be differentiated from other marks of

similar size.

Apart from the omission of the leopard's head the main

difference between the teaspoon mark and that used on other

plate is in the shape of the punch in which the sterling lion is

engraved. Whereas on all marks, other than those designed for

tea and other small spoons, the lion is in a rectangular box

with an ogee base and canted top corners the lion on these

smaller spoons between 1781 and 1785 is in a roughly oval

outline. (Fig 1)

For plate other than teaspoons more than one punch, and indeed

stub for use in a fly press, of the same size was made for each

year and these punches and stubs were designed for use on

specific items and were, usually, not interchangeable although,

oddly, this rule does not hold good for sugar sifter spoons.

The punches used on sugar sifters varied and there is no obvious

reason for this variation.

Fig. 2 shows two fiddle pattern sifters of the early 19th

century. The one bearing the date letter "F" for 1801 is five

and nine tenths inches long and the one bearing the date letter

"C" for 1818 is five and seven tenths inches long. They are both

therefore virtually the same size and were both marked by means

of the fly press but on one the teaspoon stub has been used

whilst the other has been marked using the large spoon stub!

|

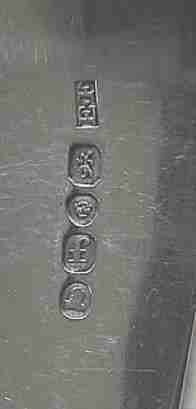

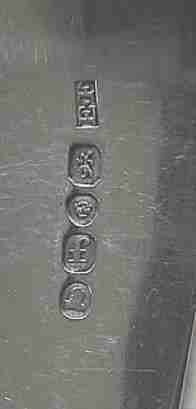

Fig. 1: Teaspoon hallmarks for 1784/5 showing

the oval outline to the lion.

(note the duty mark on the upper spoon which shows

that this spoon was

assayed after 1st December 1784 whereas the lower

spoon was assayed

between 29th May and 30th November

1784.)

|

|

Fig. 2: Top marking on sugar sifter spoons

showing different

fly press stubs used to mark spoons of similar size

|

From 1786 until 1805 the outline to the lion becomes

rectangular with a curved base and canted top corners (Fig. 3)

although in the years 1792, 1793, 1794 the punch outlines are

not well defined. From 1806 onwards the outline adopted is the

same as for other punches; i.e. rectangular with an ogee base

and canted top corners. (Fig. 4)

|

Fig. 3: Teaspoon hallmark showing the outline to

the lion in use between

1786 and 1805 (NB: This outline can appear almost

oval especially in 1792)

|

The outline of the date letter during this period

consistently has a curved base and canted top corners, (Fig. 3)

but variations in the overall shape between square and

rectangular give rise to an almost egg shaped outline in some

years, notably 1792 ( Fig. 5).

From 1805 until 1809 it, like the sterling lion, adopts the

standard canted top corners and ogee base appearance (Fig. 4).

There is no obvious explanation for the poor execution of the

engraving of the outlines to both the lion and the date letter

in the years 1792, 1793 and 1794. In neither are the canted

corners well defined but neither has been engraved in an obvious

ovoid form which would suggest an intentional deviation from the

mark outlines of the other years in this sequence. It could be

just a matter of pressure of work on the engraver and it has to

be said that the margin between canted corners and a curved

appearance is somewhat narrow especially when the mark has

become worn. Experimentation was continuing and in 1792 the

workload falling on the engraver, John Pingo, from the Company

had become so great that he had to give up his own business in

order to cope with it and this gave rise to a petition in which

he enumerates this growing workload. The following is an extract

from that petition sent to the Court of Assistants of the

Goldsmiths' Company by John Pingo in 1792 which throws some

light on this:

" ....59 Marks only were delivered in 1790 - 240 Marks

delivered in 1791 - 262 Marks delivered this day besides 39

delivered since January last, making in all 301 Marks delivered

in 1792"(see

note 1))

Was he perhaps cutting corners both physically and

metaphorically?

|

Fig. 4: Teaspoon hallmark showing the outline to

the lion in use from

1806/7 onwards and the outline of the date letter

from 1805 until 1809.

|

|

Fig 5: Teaspoon hallmark showing the date letter

outline apparent in 1792

(note that the lion outline can appear virtually

oval in this year)

|

There are obvious variations in the shape of the outline to

the duty mark in specific years but these are concerned with the

Government's increase in the amount of duty payable and for

information on this I must refer my reader to the excellent work

on the subject published by A.B.L. Dove F.S.A. in "Antique

Collecting" ( September 1984 ) and reprinted in 'Silver Studies',

the journal of The Silver Society, number 22 (2007).

The only other observations to note concerning the duty mark are

that from 1784 to 1832 the mark was engraved as the monarch's

bust and from that date onwards until duty on plate was

abolished in 1890 the mark was engraved as the monarch's head

couped at the neck. The incuse mark of George III and the mark

of Queen Victoria face to dexter and all other duty marks face

to sinister.

There is, however, one important feature to note in connection

with the duty mark and this concerns that used during the reign

of Geo IV (1820-1830). It appears that John Smith, who was by

then the Company's engraver, attempted to represent the 'quaffed'

hairstyle of Geo IV but in some years, notably 1830, has

executed the engraving so poorly that, if the bust of the

monarch is recognisable at all, it almost appears to be crowned.

(Fig. 6). It is not known exactly when Smith's eyesight began to

deteriorate but it had got so bad by 1839 that he was forced to

retire and the position of engraver to The Goldsmiths' Company

was taken by William Wyon. It may well be that poor eyesight is

the explanation for this misleading engraving and the unwary may

be tempted to think that it is a forgery. It is, however, just

one more small peculiarity to be aware of.

That in any given year the marks have been impressed in such a

way that they must sometimes be read with the bowl of a spoon on

the left and sometimes with the bowl on the right is, I believe,

of no significance since, from the point of view of

transposition, once the marks have been cut out of the spoon it

makes no difference which way round they were stamped. The order

in which they relate to each other, however, may be of

significance. The date letter on small spoons precedes the lion

between 1781 and 1785 and follows it from then on. The duty mark

is always the last in the sequence on tea spoons whereas on

sugar tongs it is the first in the sequence (Fig. 7). On larger

spoons the date letter is first in line followed by the lion

with the leopard's head next. The duty mark is always last so

that during the incuse period when it was applied before the

hall marks the latter often had to be squeezed in between it and

the maker's mark. From 1786 when the duty mark was incorporated

with the other marks on the fly press stub the sequence on large

spoons became the same as on other plate, namely; lion. leopard,

date, duty (Fig. 8).

Notwithstanding all this endeavour on the part of The Goldsmiths'

Company and that by the statute 13 Geo. III cap.59 the penalty

for transposing marks, as with other types of fraud, was

fourteen years transportation, the practice appears to have

continued and it is not surprising, therefore, that in 1805 the

committee resorted to marking large flatware in the way in which

it had been marked before 1781 with the lion at a right angle to

the other marks. The layout of the marks also adopted a vertical

format (Fig. 9).

|

Fig. 6: Hallmark for 1830/1 showing the

engraving of

the King's bust duty mark with crown like hairstyle.

|

|

Fig. 7: Press mark on tea tongs showing the duty

mark first in the sequence

|

|

Fig. 8: Tablespoon by George Wintle London

1801/2 showing the order of marks from 1786/7

|

It must have been considered that the omission of the

leopard's head on teaspoons and sugar tongs would suffice to

protect against their use for transposition but alas this was a

forlorn hope. Helmet cream jugs mounted on square plinths can be

found marked along the foot rim. Such marks are not only in the

wrong place but will be seen to be missing the Leopard's head

mark indicating that that part of the foot rim started life as

the stem of a teaspoon and that the jug was never assayed.

In 1810 the layout of the marks on teaspoons and sugar tongs

became the same as for larger flatware, i.e. a vertical stub was

used but with the marks in the order lion, date, duty and

although the lion outline retained its ogee base that of the

date letter reverted to the curved base appearance. It was not

until 1821 that the decision was taken to add the leopard's head

to this sequence which then became leopard, lion, date, duty.

There are two other features affecting hallmarks which took

place during the first half of the 19th. century and it is

difficult to see how either could have been connected with

security although just what they were connected with I have been

unable to determine.

Firstly, in 1821 the Company's engraver, John Smith, was

instructed to make "experimental" stubs as well as the regular

ones. The alterations chosen were to make the sterling lion

passant instead of passant guardant and to deprive the leopard,

which appeared for the first time on tongs and teaspoons in that

year, of its crown.

This arrangement applied only to the vertical marks used on

flatware. When the new marking year started the new regular

stubs were used but the committee soon approved the experimental

press marks and they therefore came into permanent use. Thus

1821 is known to collectors as the year in which the leopard

lost its crown but because the introduction of the new stubs

took effect after the marking year had started there are pieces

stamped in that year with either the crowned or the uncrowned

leopard. (Fig 10)

In 1822 all stubs and punches were engraved in this new way and

this format has remained in use for marking all plate since then.

There is one other peculiarity which was introduced on the

experimental stubs and that is that the outline to the lion

became a rectangle with canted top corners and a curved base on

large flatware, Fig. 11, but the ogee base to the lion outline

remained in force on small spoons and tongs until the end of the

1821/2 marking year. The new, curved base, outline came into use

on these items in the marking tear 1822/3 and remained in use on

these until1826. The lion outline reverted to the canted top

corners and ogee base format on large flatware in 1823 and 1824

but returned again to the curved base in 1825. From 1826 onwards

it had the ogee base which became the standard pattern for all

stubs and punches.

The other, somewhat baffling, feature is what has been described

as "the punk leopard". Between 1834 and 1839 the leopard has 'hair'

which appears to stand on end in what can only be described as a

'punk' style (Fig 12). It has been suggested that this feature

was an accident accounted for by Smith's failing eyesight but

the hairs are much too carefully and neatly engraved to be an

accident and besides they are reproduced in exactly the same way

in each of the years mentioned.

|

Fig. 9: Large spoon of 1805 showing vertical

marking

|

|

Fig. 10: Hallmarks on sugar tongs showing both

the crowned and

the uncrowned leopard's head used in the 1821/2

marking year.

|

|

Fig. 11: Tablespoon possibly by Edward Farrell

London 1821/2 showing the marks used on large

flatware (uncrowned leopard, the lion passant and

the changed shape of the outline to the lion).

Note the curved base appears to have been created by

canting the bottom corners.

|

Furthermore it seems that Smith was experimenting with this

form of the leopard from the moment it lost its crown in 1822,

long before his eyesight is known to have been failing. During

the later 1820s he engraved the leopard on the punches used on

large plate in two forms. In one the leopard is bald and clean

shaven and in the other it has whiskers and the suggestion of

hair. It is likely that pieces will be found marked in either

way but both are genuine. This peculiarity does not appear on

the vertical stubs used on flatware. I thought at first that

this was a satire by Smith on William IV who was known to have a

'bouffed' hairstyle and, in fact, was known as Pineapple Head.

However he came to the throne in 1831 and was gone by 1837 when

Queen Victoria acceded to the throne so that theory hardly holds

water. I have puzzled over this for some years and have found

nothing in the minute books at Goldsmiths' Hall to throw light

on this oddity. I have to admit that I cannot come up with a

satisfactory explanation.

Although the early representations of the leopard are quite

obviously of a male lion, during the latter part of the 18th

century the leopard takes on an almost human appearance and in

the early 19th its crown has the three points of a jester's hat

making it look like a jester (Fig. 10). After 1821 the leopard's

visage takes on a troll-like expression and the most likely

explanation for these variations is that the engravers had never

seen a leopard! The more modern representation is quite catlike

and easily recognisable.

|

Fig. 12: Hallmarks for 1835/6 showing the

'Punk' hairstyle of the leopard's head

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am indebted to the Worshipful Company Of Goldsmiths for

allowing me the privilege of examining their records.

David McKinley

- 2014 -

David McKinley devotes much of his time to

researching the history of silversmithing in England

with particular reference to hallmarking at the London

office. He writes for both The Silver Spoon Club of

Great Britain and The Silver Society.

David McKinley is the author of the book THE FIRST

HUGUENOT SILVERSMITHS OF LONDON

Information about the content of this book and the

discounted price applied to members of ASCAS is

available in

September 2011 Newsletter

|

|