by Martine

D’Haeseleer

(click on photos to enlarge images)

Silverware from the Belgian Workshop

Wolfers Frères

in the Belle Epoque Period

American collectors and specialists in silver usually know

much about French, English, Austrian and German silver, but are

relatively less informed about Belgian silver. This article

about the highly skilled, abundantly ornamented late 19th

century silver from the workshop of the Belgian silversmith

Wolfers aims at closing that gap. It is largely based on my

lectures to younger generations of art lovers over a period of

ten years, through which I have endeavored to open the door to

the discovery of the quality, personality and creativity of

Belgian Silver, particularly that which was made during the

so-called Belle Epoque.

Belgian Belle Époque Silverware

Wolfers Frères’: Jewelers and Silversmiths

Strategically situated on fertile soil at the crossroads of

Western Europe, Belgium has enjoyed economic prosperity,

artistic creativity and a strong tradition of skilled

craftsmanship. It is a small country enriched by the

interweaving of different ethnicities and cultures--a true

melting pot of populations. Surrounded for centuries by France,

Germany, the Netherlands and the North Sea, this “slice” of land

was highly coveted by its neighbors and it was not until 1831

that it achieved true political independence. Since then,

successful industrial development has brought prosperity to an

expanding middle class that was already much in evidence during

the Belle Époque. The words of the Belgian singer, Jacques Brel

“C’était au temps où Bruxelles Brussel ait… “, imply that people

of the Brussels middle class were wealthy, prosperous and

enjoyed life at that time.

Wolfers was one of the most famous Belgian silversmith companies

of the 19th century, its reputation comparable to those of Emile

Puiforcat, Odiot or Aucoc in Paris, Garrard in London, and

Tiffany or Gorham in America.

In the first half of the 19th century, three young German

brothers, silversmiths Edouard, Guillaume and Louis Wolfers

established two workshops in Brussels.

|

In 1852, Louis Wolfers (1820-1892) registered his

maker's mark, consisting of a letter W above a boar's

head. His workshop was situated at 23 rue des Longs

Chariots.

In 1858, he married Henriette Ruthenburg who contributed

to the development of the firm. They took part in many

different exhibitions and competitions and, by 1868, the

firm was achieving financial success.

After serving apprenticeships, their three sons,

Philippe, Max and Robert were sent to France, Germany,

the Netherlands and Austria to prospect for business.

As a result, the Wolfers firm became associated with

Bonnebacker of Amsterdam, P. Kirscher in Düsseldorf,

Goldschmidt in Köln, and Friedlander in Berlin. This

explains why some German assay and retailers marks are

punched with Wolfers marks.

|

|

Louis Wolfers maker’s marks (1852-1892)

|

In 1885, Philippe Wolfers married Sophie Wildstädter. His

bride’s dowry enabled him to become a partner in his father’s

business. The firm was renamed ‘Louis Wolfers Père et Fils’. By

1890, Max was playing an active role in the business. The

workshop and shop moved to the Rue de Loxum.1 and the new shop's

mark: "Louis Wolfers Père et Fils’ Rue Du Loxum 1 Bruxelles" was

conjoined with the former maker’s mark. In 1892, after Louis

Wolfers death, the firm was renamed ‘Wolfers Frères’.

In 1892, the new maker’s mark, three pentacles

(5-point stars) contained in a triangle, was introduced

and continued to be used until 1942. It is a rare

example of a personal mark using Masonic symbols.

|

|

| |

Wolfers Frères’ Workshop and maker's marks

(1892-1942)

|

In 1897, Robert Wolfers persuaded the firm to

install hydraulic presses for the production of flatware.

Philippe, the artistic director, played a very important

role in the development of the Art Nouveau in Belgium.

Various jewelers were exclusive agents for Wolfers

products.

For example, E. Antony in Antwerp, E. Bourdon in Ghent,

F.Hardy in Liege, Galerie Aublanc in Paris, and Begeer

in Utrecht.

Branches were opened in Budapest and Bucharest.

Wolfers silver was also imported into Russia.

|

|

| |

Waterjug, maker Wolfer frères, ca.1892-1900

|

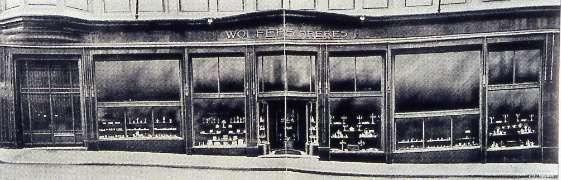

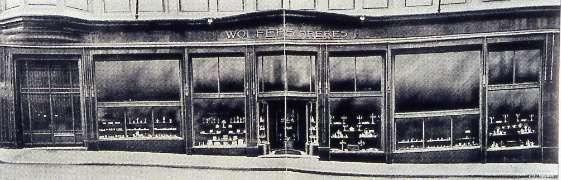

In 1907, the Wolfers firm employed about 150 workers. They

moved the shop and workshop to the rue d’Aremberg where the

famous art nouveau architect, Victor Horta, designed a new

building for them. This beautiful building still stands on the

left of a KBC Bank branch and one can admire the shop’s

furniture at the Musée du Cinquantenaire in Brussels

|

|

Wolfers' shop, rue d’Arenberg 11-13 Brussels,

1911 Architect, Victor Horta.

|

Decorative Arts Styles

An older generation of collectors

considers only 16th, 17th and 18th century silver as genuinely ‘antique’;

19th century silver is considered decadent because of industrial

production that overtook centuries of handmade silver and also

because the emerging 19th century middle social class (i.e., the

‘bourgeoisie’) favored reproductions of 18th century styles (e.g.,

neo-Louis XV or neo-Louis XVI styles)--they wanted to copy the

good taste, manners and ways of thinking of the former

aristocracy and, perhaps more importantly, because they wanted

their silver to reflect their own success and prosperity. The

neo-Louis XV style is often called ‘Rococo’ in a rather

disparaging way, but the term was already in use referring to

18th century Rocaille, an extremely eccentric interpretation of

the Louis XV style.

The so-called Eclecticism of the 19th century is unquestionably

a combination of Louis XIV or Louis XVI patterns with Louis XV

and Rocaille. Yet, if instead of name-calling, we analyze the

styles throughout the different centuries we observe that

evolution of styles does not stop or start abruptly but instead

glides smoothly from earlier forms toward the introduction of

new decorative elements. In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries,

symmetric, geometric, asymmetric, and floral styles alternately

followed one another.

The Louis XIV style, for instance, was (in a way) a

neo-classical style, influenced by Renaissance architecture and

ornamentation. Similarly, we find 18th century LouisXV and

Rocaille styles reproducing naturalistic motifs of 17th century

Mannerism and spirally fluted Louis XV forms mixed with

‘in-fashion’ Louis XVI motifs.

The quality of 18th century handicraft

is often idealized and the creations of 19th century

silversmiths underestimated. J.F. Hayward in Virtuoso Goldsmiths

said, 'Considering the working methods, we have to put aside

romantic conceptions of the nobility of handwork. The goldsmith

took as much interest in methods of increasing efficiency and

reducing costs of production as any modern factory manager.

Different processes like casting, turning on a lathe or

producing ornaments by means of a stamp were all in use by the

second half of the 16th century'.

Indeed, why should we be so formalist, critical and negative

about the 19th century neo styles? Typical rococo revival was in

fashion in many different European countries, mainly Belgium,

Germany, Austria and even in the Netherlands. The neo-Louis XV

style with its spirally fluted lines was adorned with Rocaille

motifs that were exuberant with crested motifs looking like the

fringe of falling water, or the crest of sea wave and

asymmetrical Rocaille cartouches. Flowers, daisies and reed

flowers were added and rendered even more flourish to the

ornamentation . These crested patterns find their origin in the

influence of Japonisme

|

|

|

Detail of Rocaille motif Waterjug

maker: Wolfer frères, ca. 1892-1900

|

Detail, Reed Motif Waterjug

maker: Wolfer Frères, ca. 1892-1900.

|

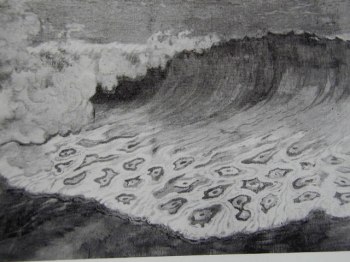

The wave, as a pictorial theme and

ornamental pattern in Japanese art, had a profound impact on

European painting, graphic art and applied arts in the second

half of the nineteenth century. The crest of the wave motif

belongs to this form.

Philippe Wolfers became familiar with Japanese art through the

opening of ‘La Maison Japonaise’ in Brussels (1866) and the

Vienna world exhibition in 1873. His silver was mostly heavy,

cast or hammered; the decoration chased and engraved. Wolfers’

workshops employed highly skilled workers; there was no room for

low quality stamped production

|

|

|

|

Sauceboat: maker, Wolfers Frères, ca.

1892-1900.

|

Ice serving dish: maker, Wolfers frères, ca.

1892-1900.

|

Strawberry dish: maker, Wolfers frères, ca.

1892-1900

|

Influence of Japonisme

In order to be credible in stating

that the influence of Japonisme is found in the ornamental

motifs of Wolfers Frères’ silverware at the end of the 19th

century, I have taken a few quotes from the the text of the book

‘Japonisme: The Japanese influence on Western art since 1858’ by

Siegfried Wichmann.

The wave as a pictorial theme and ornamental pattern in Japanese

art had a profound impact on European painting, graphic art, and

applied arts in the second half of the nineteenth century. The

highly stylized wave formula, underwent an intensification of

decorative force in Europe, especially in the Art Nouveau

movement ...

The motifs of the crest of the wave and of individual swirling

eddies both belong to this form and both lend themselves to

quasi-geometrical treatment...

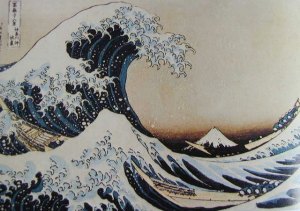

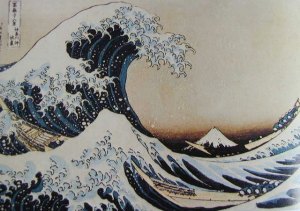

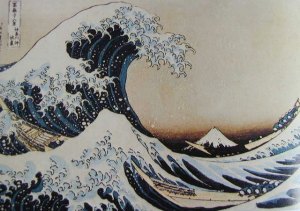

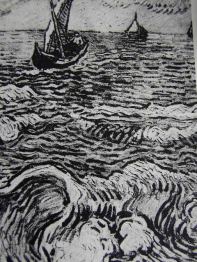

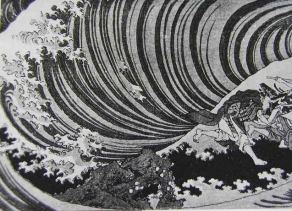

The wave as the subject of a painting is perhaps best known in

Katsushika Hokusai’s 'The Great wave off Kanagawa,'

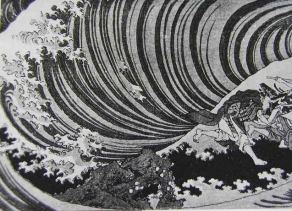

woodcut (1823-32), Totoya Hokkei, ‘Mekari Festival,'

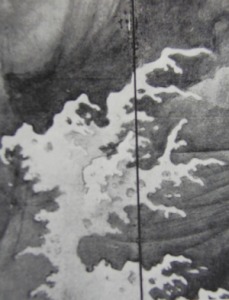

color woodcut (1830), Maruyama Okyo, 'Screen with Dragon and

wave Pattern' (1780) and 'Japan ‘Stormy sea’ (detail)

|

|

|

Katsushika Hokusai: The Great wave off

Kanagawa

Woodcut (1823-32)

|

Totoya Hokkei: Mekari Festival

Colour Woodcut (1830)

|

|

|

|

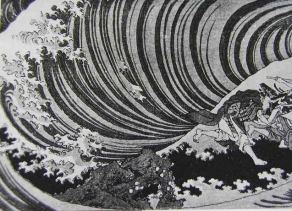

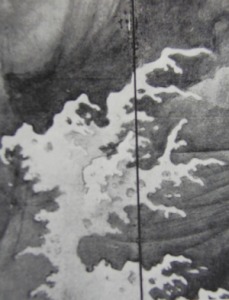

Maruyama Okyo: Screen with Dragon

and Wave Pattern (1780)

|

Maruyama Okyo: Japan ‘Stormy sea’

(detail)

|

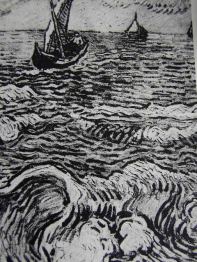

European Painters and graphic artists

(and industrial artists too) produced many variations on the

wave theme around the turn of the century….

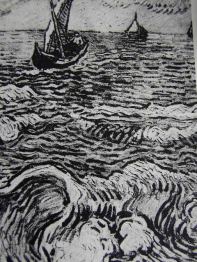

Van Gogh introduced this almost calligraphic wave shape into

painting in quite a different

manner, yet still in an impasto’ technique... (in) 'The Sea at

Saintes-Maries- June1888…' .

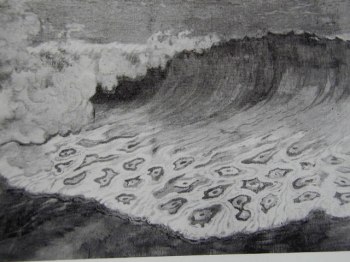

Georges Lacombe(1868-1916) also gives a detail of a breaking

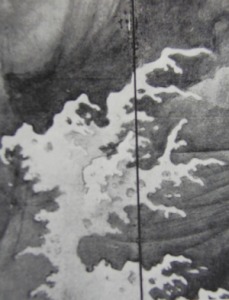

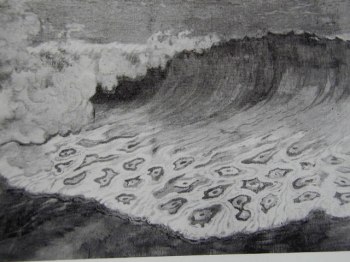

wave which is clearly influenced by Japan. …. Here is a detail

of a wave seen both realistically and yet a the same time

decoratively

|

|

|

Vincent Van Gogh

The Sea at Saintes-Maries (June1888)

|

Georges Lacombe

detail

|

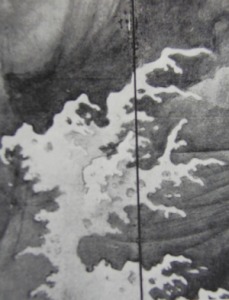

I will now draw a few parallels with

photographs of ornamental details from Wolfers' silver

|

|

|

Water jug-detail

|

Katsushika Hokusai: The Great wave off

Kanagawa

|

|

|

|

Handle of the sauce boat

|

Georges Lacombe: detail

|

|

|

|

Details of Ice cream dish

|

Maruyama Okyo: Screen with Dragon and Wave

Pattern (1780)

|

|

|

|

Details of Ice cream dish

|

Maruyama Okyo:Japan 'Stormy sea' (detail)

|

|

|

|

Bonbonnière

|

Vincent Van Gogh: The Sea at Saintes-Maries

(June1888)

|

|

|

|

Shell-dish

|

Totoya Hokkei and Maruyama Okyo

|

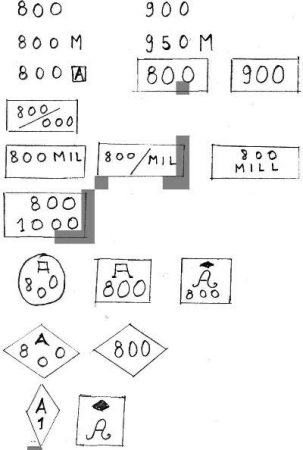

Belgian Silver Marks

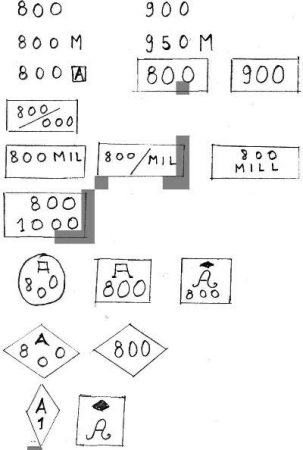

I conclude with a few notes on Belgian

silver marks for those who have been persuaded to take a further

'in vivo' look at Wolfers’ magnificent creations. To defend

against severe competition of imported silver from France and

Germany, the Belgian silversmiths petitioned for a change in the

laws governing their work. As a result, 1868 to 1942 became a

period of great liberalism: official silver standards were

lowered to 900 and 800, no Hallmarking office assay was needed

and, there was no registration of personal marks. As an

unintended consequence of this liberalism, it is today difficult

to identify Belgian silver from that period because each of the

silversmiths and retailers used their personal assay marks.

A silver object is guaranteed by means of two marks: the silver

standard and the maker-manufacturer or retailer’s mark. In

Belgium, the former included the gothic letter 'A' for Argent (silver)

and either a number 1 or 2 for the silver standards, 900 or 800,

respectively (from Tardy, Poinçons d’argent’).

|

|

|

Belgian official assay marks for silver:

1st standard period (1868-1942)

|

Belgian official assay marks for silver:

2nd standard period (1868-1942)

|

Manufacturers and shops also created

and used a wide variety of other content indications, such as

from 800 to 950 punched alone or combined with the letter A or

combined with a symbol representing the standard in thousandths

(i.e.:Millièmes) (M; Mes; MIL; 1000). As stated above, one often

finds German assay marks (such as the moon crest or the imperial

crown) as well as German retailer’s marks combined with Wolfers’

Belgian marks.

|

|

Belgian silver standards mark for large

items (1868-1942)

(Personal research work)

|

|

The Imperial Crown and the Moon Crescent German

State marks in use since 1888

|

Bibliography

Orfèvrerie au Poinçon de Bruxelles’,

1979, Exhibitions Catalogue Societé Générale de Banque - 13/09

au 30/11 1979.

‘Modern Silver 1880-1940’, Amsterdam 1989, A.

Krekels-Aalbeerse.

‘Silver of a New Era, International Highlights of Precious

Metalware from 1880 to 1940’ Museum Boymans Van Beuningen,

Rotterdam. Museum voor Sierkunst, Ghent 1992.

‘Philippe und Marcel Wolfers’, Art Nouveau und Art Déco

aus Brüssel, 1993-1994, Museum Bellerive Zürich.

‘Van Belle Epoque tot Art Nouveau’, Antwerp 1998, Wim

Nijs, Sterckshof Studies 10

-Belgian Silver 1868-1914. Provinciaal Museum

Sterckshof-Zilvercentrum. Antwerpen-Deurne ISBN 90-6625-007-0.

‘Royal Silver for People and King’, Antwerp 2001, Wim

Nijs, Sterckshof Studies 17.

Provinciaal Museum Sterckshof-Zilvercentrum Antwerpen-Deurne

ISBN 90-6625-028-3

‘Silver’ 1880- 1940 Art Nouveau-Art Déco', Amsterdam

2001, Annelies-Krekel-Aalberse, Arnoldsche

ISBN 3-89790-161-7

‘Les Wolfers Orfèvres, Bijoutiers & Joaillers’, Walter

van Dievoet, Brussels 2002, Edition STUDIA BRUXELLAE

‘Japonisme’ The Japanese influence on Western art since 1858'

Siegfried Wichmann – Thames and Hudson- New York-NY

Photo Credits

All pictures are ©Martine D’Haeseleer

- Many were digitalized by: Studio Durieux - Belgium

Exceptions:

Wolfer hallmarks 1852-1892 and Brussels' shop: ©Catalogue ‘Van

Belle Époque tot Art Nouveau’ Sterckshof Museum’ Deurne

Antwerpen.

Wolfers' centerpiece Aux Maraudeurs--‘Puti playing with snails’:

Courtesy of the Antique Dealers ‘Pash and Son’ – London

Images illustrating 'Influence of Japonisme': © Book :

’Japonisme’ The Japanese Influence on Western art Since 1858-

Siegfried Wichmann – Ed. Thames and Hudson

Martine D'Haeseleer

www.silverbel.com

Text edited With the great and kind help of Ricardo and

Janet Zapata, New York Silver Society

This article was originally Edited with efficient and

friendly help of Marberth Schon

'Modern silver Magazine' March - May 2006 -

www.modernsilver.com

|

|

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER

ASSOCIATION OF SMALL COLLECTORS OF ANTIQUE SILVER