by

Jeffrey Herman

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JEFFREY HERMAN was just elected into the

prestigious Fellow category of the Institute of

Professional Goldsmiths in England. He's the only

Fellow living outside England. Herman was nominated

by three other Fellows of the IPG, and humbled that

these Fellows felt him worthy of this honor.

This is his 30th year in business operating as a

silversmith specializing in restoration,

conservation, and preservation, and 25th year as the

Founder of the Society of American Silversmiths

(SAS).

Jeffrey Herman worked at Gorham as designer, sample

maker, and technical illustrator. Upon leaving

Gorham, he took a position at Pilz Ltd where he

learned the fine art of restoration, and fabricated

mass-produced ecclesiastical ware. He earned a BFA

degree in silversmithing and jewelry making from

Maine College of Art in Portland, studying under

Harold Schremmer and Ernest Thompson, two

outstanding designer/craftsmen. He started his

business in 1984 gaining a national reputation of

quality craftsmanship repairing and reconstructing

everything, from historical pieces to single spoons.

Further details about Jeffrey Herman and information

contact are available in his website at

http://www.hermansilver.com

|

(click on photos to enlarge image)

THE BEAUTY OF PULSE ARC WELDING

As any silversmith

knows, silver solder is the ideal material to

use when joining sterling pieces by the

traditional method of brazing. Sometimes I will

receive an object which has been lead-soldered

in the area in need of repair (or re-repair).

Sometimes the joined area is not visually

accessible, and I don't know if lead has been

used.

In either case, I cannot use silver solder

because the high temperature required will melt

any lead in the joint and allow it to form its

own alloy with the silver. Not pretty! And,

using a low temperature tin/silver solder won't

give me a sound joint or good silver color.

For this reason, I use the German-made Lampert

PUK 3s Professional Plus pulse arc welder. Pulse

arc welding allows me to use solid sterling wire

for a perfect color match (silver solders

contain less fine silver than sterling).

|

The pulse arc welding

principle: Non-toxic argon gas is pumped through

a handpiece and engulfs the welding area with a

protective atmosphere to eliminate firestain. An

electric arc (energy flow) is created from the

point where the electrode touches the workpiece.

As the electrode retracts, the arc is drawn up

from the point of contact. Exactly here, melting

occurs, and the result is a clean and stable

weld.

The high degree of precision is made possible by

touching the workpiece with the tip of the

electrode. The electrical arc necessary for

welding is thus generated from exactly this

point. By varying the angle at where the

electrode tip touches, welds can be accurately

steered in the desired direction and previously

applied metal "distorted" or modeled. The heat

is so localized that I can handle the object

without getting burned, even at 1,640 degrees -

the melting point of sterling!

|

This 5 1/2" Wallace

sterling cut glass jar cover was stamped and spun

out of extremely thin material.

The image on the left shows light coming through

three areas of a flower as well as other areas on

the piece.

These areas were worn through from over polishing.

The edges of the open spaces were the approximate

thickness of a piece of tin foil.

The PUK worked beautifully, and I used .25mm

sterling wire for a perfect color match.

|

Someone had the clever

idea to engrave these 1730 caster bodies with "salt"

and "pepper". (The tops were left off to show a

larger area of the engraving.)

Engraving the function of these pieces is certainly

not something I would have done, but to each his own.

Since the engraving was too thin to remove by filing,

I used sterling wire and the PUK to fill it in.

When I photographed the "after" image I had not yet

polished the bottom sections of the casters (and the

change in the tarnish color is due to the casters

handling while welding). The total time it took to

fill in the engraving, repatinate, and hand finish

the casters was three hours.

|

This rare Jensen piece

shows chased lettering that I filled in with

sterling (left). The image on the right shows the

finished job. A few pin pricks were left to blend

with the rest of the surface. If this hadn't been

done, the filled surface would have looked too

refined.

|

This ring's amber was

glued onto the setting with decorative wires above,

only 1/16" from the stone.

As you can see in the image on the left, the wires

had come apart. Since I couldn't remove the stone, I

had to weld the wires back together with the stone

in place.

Here's the process I used: I pried open the wires

and removed the silver solder. The wires were then

sprung back together.

I slid index card stock between the wires and the

amber to prevent the stone from burning during

welding.

The wires were then welded together with sterling

filler wire.

|

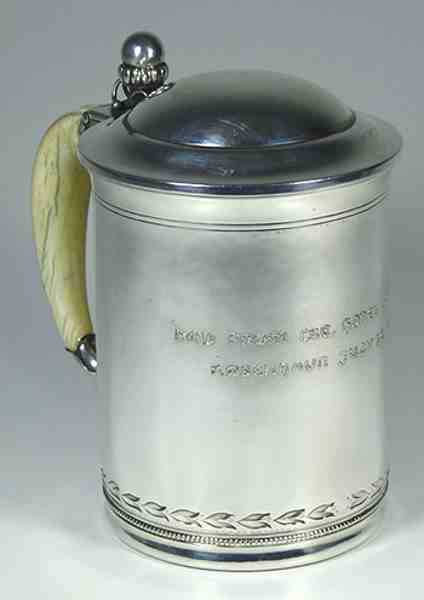

This Meiji-era teapot

needed its handle secured and its dents removed from

the single-walled body, double-walled cover, and

removable tea strainer that sits under the cover.

There had been a rod extending through both ivory

insulators. One end was hard soldered to the handle

and the other was peened over on the inside of the

pot. Over time, this assembly loosened.

I removed both rods then welded new ones to the

body, covering the holes.

I then drilled holes through the handle for the rods

to extend and countersunk the holes.

After I reinstalled the insulators over the rods, I

attached the handle with the rods protruding through

the holes.

I then pulsed down over the rods, spreading the

silver into the countersinks and securing all parts

for an undetectable repair.

|

|

|